The Summer of Bob

Imagine hearing his voice for the first time. Again.

I don’t know what year it was, but it was the Summer of Bob.

Maybe I was thirteen. My brother and I spent our summers in Maine when we were growing up, and the first few weeks of vacation were always the same grueling chore of mowing the neglected, three-foot grass around our farmhouse with a small, pull-start mower that hadn’t self-propelled for years.

The two albums worked their way deeper and further into the milk crate record collection until they were forgotten entirely. Almost.

It was hot, endless work and it always felt like high noon. My back always hurt, and my hands blistered even with the old gloves, and I hated it. It made the start of every summer a predictable hell when all the other kids were stopping by son their bicycles to find out when we’d be done, which was “never” I’d tell them, looking towards our Maggie’s Farm mother who insisted on the yard work being completed.

But that Summer of Bob, Chris had the idea of moving the living room speakers out on to the back porch and letting the sound roll across the lawn where we raked. And for some reason we found the Greatest Hits albums of Bob Dylan that our mother had given to each of us on some prior Christmas and we’d never played – except that first time just out of dutiful politeness.

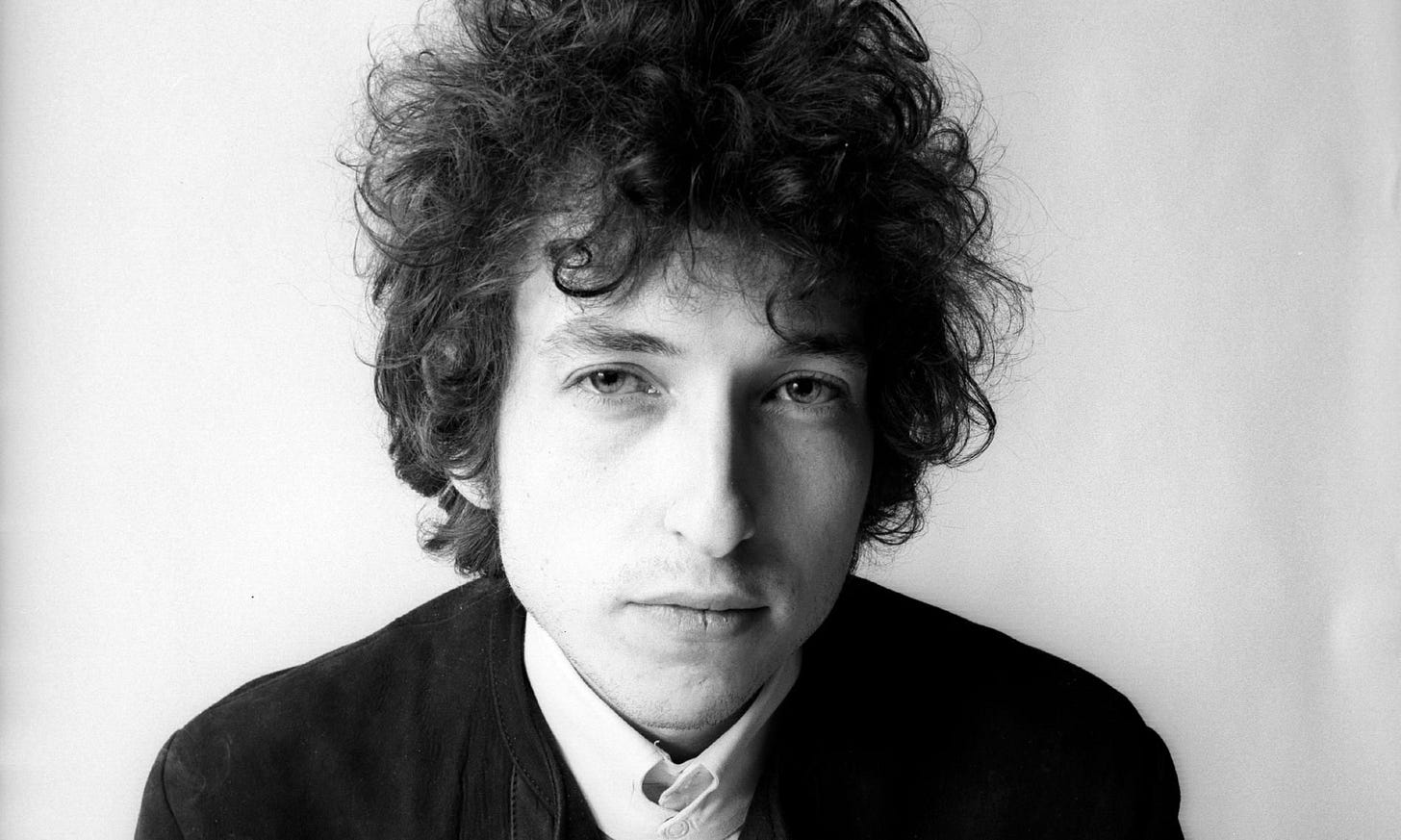

The critics write for days about his words and what means what and who’s really who, but the sound of his voice was where our appreciation of Bob Dylan started

We had been immediately disappointed with the records, the singer’s voice was intolerable, and the double album which was given to me was even worse because it held twice the promise and twice the disappointment. A bust. Two busts. The two albums worked their way deeper and further into the milk crate record collection until they were forgotten entirely. Almost.

Except the Summer of Bob one of the albums was given another try, and then the other album side, and then both albums, and then this odd singer in the blue hair light with the harmonica contraption started to grow on us. We were doing impressions of him to amuse each other over long summer dinners and learning verses that made our mother laugh from the kitchen.

The critics write for days about his words and what means what and who’s really who, but the sound of his voice was where our appreciation of Bob Dylan started – or his voices because his sounds are plural, and he has reinvented his sound and his voice with the prodigal restlessness of a Picasso – with as much success.

We learned his words, his phrasing, his attitude, his sly humor. We looked up from our raking to watch the harbor flow. We became him singing his songs. We’d head back inside the house dragging grass into the living room to flip the record or replay the same side endlessly. We couldn’t get enough.

My brother and I couldn’t possibly know that his voice would follow us the rest of our lives, surviving the death of our mother, the loss of the summer house, and now holds at a steady distance, skirting the hilltops, as faithfully as the moon tracking your car.

Oh, my God. Who was this guy? Other than one or two songs, we hadn’t really known his music from the radio. We didn’t know if the songs on those greatest hits albums were from the previous year or two decades earlier. For us wasn’t associated with any political movement. We knew nothing of his celebrity or personal dramas or love affairs. There was no Rolling Thunder tour, no Joan Baez, no scandal at Newport, no Christianity, no flipping snidely through words on flash cards, no myth or image apart from what came through the songs and the voice.

The voice. That was it. We didn’t know anything except that he was a voice we understood and felt, and his voice spoke for the sensitivity and intelligence of our family.

And so, Bob Dylan came into our lives and settled down with us collectively and individually, and it felt to us, knowing so little about the actual man behind the songs, that he was born within the walls of our summer home, arriving outside of time, and playing through our old speakers. He took up permanent residence in the memory of that home and our long summers there.

His is a strange and enchanted fairy-tale instrument, roughly bowed with the raised hair of your spinal cord.

You couldn’t help but imitate his voice. Its burry edge got under your skin, won you over with its confidence and razor-focus, but it always operated on you peripherally somehow in ways he probably does not understand fully himself. His is a strange and enchanted fairy-tale instrument, roughly bowed with the raised hair of your spinal cord.

There is more than one great novel where the love of someone’s life turns out to not look at all what the hero of the story expected, and our love for the sound of Bob Dylan arrived in our family’s life like that, hitting us from below, easy and slow, straight on target, so direct, and rolling out over the tall grass that summer.

My brother and I couldn’t possibly know that his voice would follow us the rest of our lives, surviving the death of our mother, the loss of the summer house, and now holds at a steady distance, skirting the hilltops, as faithfully as the moon tracking your car.

Buried In the Mix: "Shelter from the Storm"

A Divine Screech At 3:02 in The Rolling Stones Gimme Shelter, Merry Clayton's lets loose the word "murder"and her voice breaks. Call it a Divine Screech. Call it the Voice-Crack Heard Around the World. Immediately after, you hear the band whoop with excitement in the background.

Muddy Waters: Mannish Boy

When Robbie Robertson asked Muddy Waters to participate in the filmed concert that was to become The Last Waltz, Muddy Waters agreed with the condition that Waters would bring his own rhythm section to back him. Robertson had explained during the negotiations that the idea of the concert was that

"Beyond the Horizon" by Dylan-- a later composition that holds my heart along with everything this marvelous poet does. Thank you, Adam, for your subscription and the "like" on Chapter 1 of the memoir, a chancy exploration and how I found you and glad I did. I do hope we'll be reading each other regularly.