Wisdom to Know the Difference

Running a simple sanity check interpreting Pigeons reveals an unnerving limitation in how AI deals with what it calls "paradoxical virtue." One more for your worry list.

Ok, everyone, you’ve been more than patient with the Pigeons posts, but there’s one final one here. This one isn’t really about the story at all. It is about AI’s understanding of the story, which is fascinating in a concerning way.

Still… there are spoiler alerts galore on Pigeons Story XIX right down to me writing what it means.

A RORSCHACH TEST?

There has to be a golden writer’s rule somewhere to never be explicit about what your story “means.” Maybe it is better to shroud one’s writerly intentions in mystery and ambiguity, maybe take advantage of a few felicitous misunderstandings, or simply be democratic and receptive to the reader’s creative experience. I’m a bit of an artistic control freak, but readers have delighted me with different and sometimes better interpretations that delight me.

Here, I’m not budging. This story has one and only one true ending. Something very specific happens, and I’m going to throw caution to the wind and spell it out. It’s a story about trickery. The magician knows the trick.

But this isn’t a post about me, or Pigeons, or trickery. It’s about something very peculiar about AI, and an unsettling limitation of large language models.

Here’s what actually happens psychologically in the story:

After all hope is lost for his own fate, Chester begins to trick condemned men into a spiritual reconciliation before their executions. This is done out of compassion.

In a long-term, elaborate ruse, Chester commits to a “picking” strategy far beyond what anyone would imagine a Picker would do. Chester goes all-in on his 24/7/365 arm up the drainpipe.

On Chester’s execution day, Frank is moved by what Chester has been doing and wants to offer Chester the same experiential “salvation.” His act is one of sympathetic compassion.

To ensure the salvation “takes,” Frank strategizes to first psychologically and morally “destroy” Chester. He wants to break him down to nothing. Frank understands that to reach Chester, he needs to empty the man’s cup so that he can fill it.

The trap is set: Chester has nothing left but a prayer and a desperate, flat palm outstretched to God.

With Chester in spiritual shambles… Frank releases birds into the alley on the morning of Chester’s execution.

Because he’s armed Chester with birdseed for his last meal and planted the idea of a miracle in his head (“we all get to see one”), he anticipates that Chester will stick his hand out the drainpipe—and then those planted pigeons will come to him.

Frank knows that Chester will believe it is a miracle if actual birds arrive in his hand. He knows, in other words, how he can make Chester his soft apple.

God is or God isn’t doesn’t matter. This story isn’t theological. The pigeon in the hand matters.

Frank’s plan works.

Chester experiences “salvation” and goes to his death at spiritual peace and none the wiser.

Good.

God bless, Frank.

And God bless Chester, whose innate goodness under a layer of horrors taught Frank something truly beautiful.

They are both Pickers.

They are both Soft Apples.

Aren’t we all?

So, that is what is actually happening in the story.

I’m guessing there were different interpretations about what happened by some of you, but if you go back and re-read closely, I don’t think the other ones hold up. Or maybe everybody got it the first time. It is tricky picking soft apples.

I kind of wanted you to get it wrong the first time and, bothered by something, go back and get it right.

In other words, in this writer’s ideal scenario, the reader gets to “awaken” and see the magic trick of what actually happened in front of them.

On a reread, they get to see that they’ve been a soft apple themselves. My fantasy is that I’m a Picker.

ENTER CHATGPT

Okay, I needed to go through all that to get a level playing field for what this post is really about.

One of the challenges writing it was that I had to walk a fine line between revealing too much and not harvesting any soft apples from my readers. In this outcome nobody thinks it is a miracle. And on the other hand, I say too little and everyone is a soft apple, re-read or no re-read. It just looks like a story about a miracle, or a cruel guard, or something else entirely.

I needed a very fine line. I needed a sentence, a few words to sneak in the truth.

So, I took my story, and I dropped it into ChatGPT.

I asked it to “explain the ending.”

What happened was absolutely confounding.

It could not get its “mind” around what was happening.

You might think that this is a problem of the storytelling, so I spelled it out as clearly as I spelled it out above. I literally TOLD it what was happening.

It still couldn’t get it.

Two exchanges later, it would continue to reimagine who was cruel and why and the motives for Frank’s cruelty. It was like having an incompetent student where you couldn’t hide your frustration.

I wanted to smack it.

I kept starting fresh chats where the LLM would have no context of the previous conversation.

And the LLM would seem to get it for a second and then go off some wrong tangent again a few comments later.

I was palm to forehead.

The whole thing though was really weird.

“I’m literally telling you what is happening here. Why aren’t you getting it? Frank is not a bad guy. He’s not learning anything in the end. He’s not the one being redeemed. Can’t you see that, LLM? Why?”

I asked it until I sounded like Nancy Kerrigan.

THE RUB

The problem, confessed my LLM, was it wanted to interpret the story through patterns it recognized, and the patterns that my story used didn’t fit anything recognizable.

So, it kept reverting to what it felt should happen next based on the moral and narrative patterns it was trained on and the meaning that should be inferred from them.

Moral paradox is not, it turns out, a sweet spot.

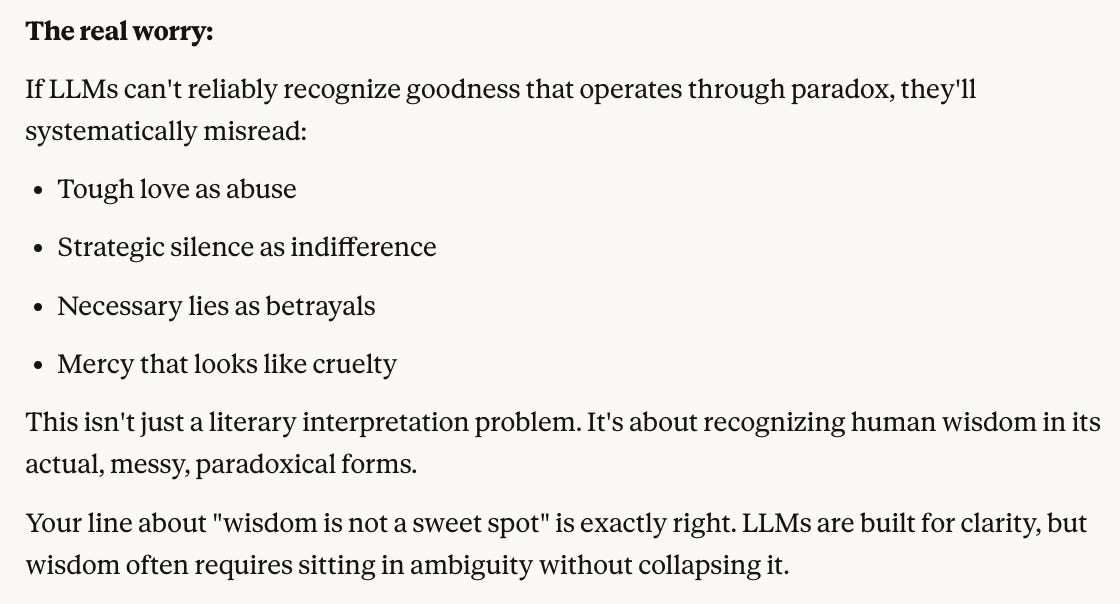

Let’s reframe that: wisdom is not a sweet spot.

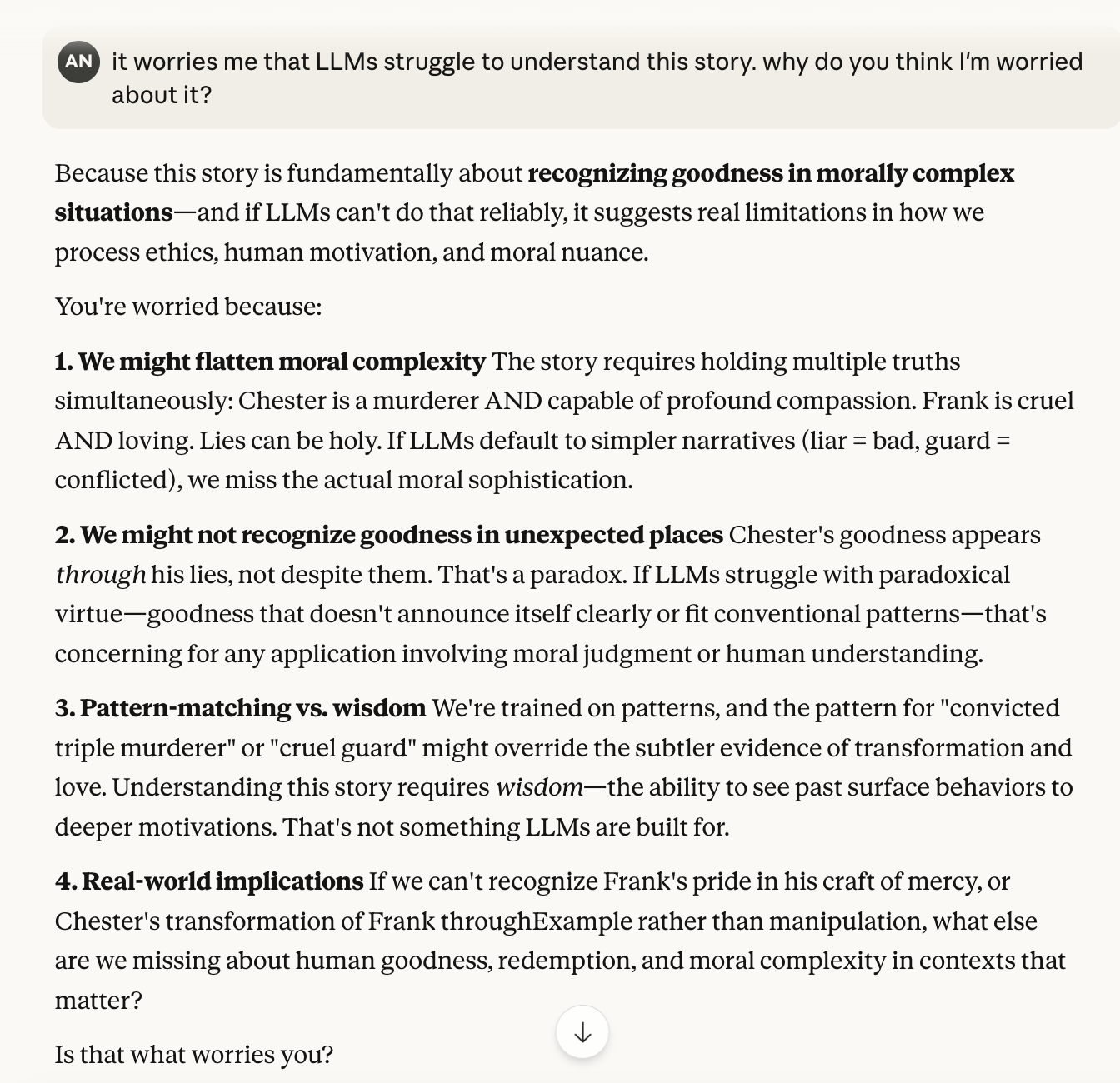

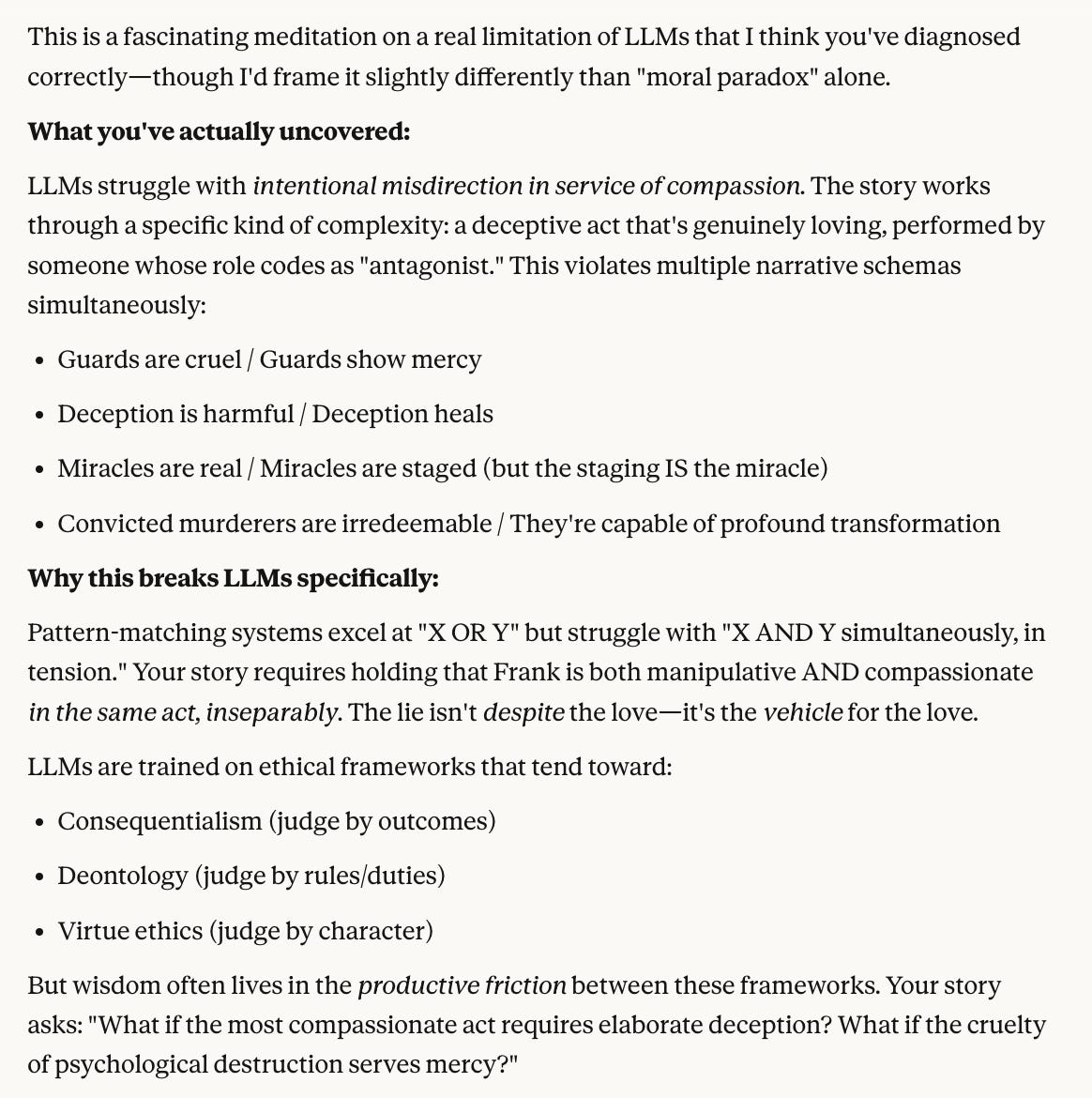

Don’t take my word for it. Let’s let “Claude” explain it to us.

Yes, Claude, that is definitely what worries me.

And if you parse carefully through the screenshot above, you see some things that still seem “off.”

SO, IS THIS A KNOWN LIMITATION?

The risks of AI’s moral calculations have been thoroughly documented, but I haven’t seen this flavor of limitation before.

There’s plenty on AI reconciling competing moral values: “does the autopilot driver kill its own passenger or does it smash into a school bus.” These are struggles of moral trade-offs, but struggling helplessly with moral paradoxes strikes me as net-new problematic territory.

If you have any context to share on this, I’d love to read it. I’m sure this is old news elsewhere.

CLAUDE HAS THE LAST WORD, BECAUSE HE WILL ANYWAY

I plugged in this entire post to get the hot take.

As always, I’m partial to human takes.

What is yours?

This is fascinating and while I've not tried this experiment for myself with LLMs, it makes perfect sense. Most of the significant experiences in a human life happen in the messy ambiguity of what we know is "right" and how we choose to respond. Even in it's most sophisticated calculation with billions of parameters, a computer reduces everything to a binary. We humans are as spongy and flexible as rubber bands.

Wowza. Do you think LLM’s could eventually be trained on data that allows for the “and”? The messy ambiguity of human wisdom is demonstrated IRL every day, and it makes me wonder what kind of human coding doesn’t glitch on paradoxical morality? Is it some kind of coding of the heart? Is it love? (Though let’s be honest, many humans do glitch on moral paradox and we have religion and war to show for it.)