Threshold - II

My mother falls ill in Bergamo.

It was the school year of 1972-1973. My mother left our father in the fallout of a disintegrated marriage, and she took my brother and me to Bergamo, Italy, a medieval city nestled in the foothills of the Italian Alps.

Beyond the simple escape of leaving the chaos that fall, my mother was pursuing a diploma at the International Center for Montessori Studies. Maria Montessori’s son — and closest lifetime collaborator — founded the center specifically for the training of elementary school teachers. Mario still taught there. The training was the real deal.

To do this, my mother took a year’s sabbatical from directing the Princeton Montessori School. My mother was a pioneer in her own right. In the late ‘60s, she founded her Montessori school in the basement of a convent and grew it for almost two decades. It thrives to this day on the campus she established. I visited it when it was a dirt field and a conversation about bank loans falling through. My mother was also the real deal. I have the receipts.

Montessori was my mother’s catnip. Try this quote on from Maria Montessori: “[Teachers must] regard a child's intelligence as a fertile field in which seeds may be sown, to grow under the heat of flaming imagination." My mother would have travelled to Timbuktu to find the source of that sentence. Yes, the three of us were fleeing chaos, but my mother also directed us towards something with meaning and purpose. Her vision steadied us.

My mother had been a ballet dancer. When the world started to spin, she knew how to pick a spot on the wall.

*

She became, for those first few fall months, young again, a student. She returned to an arena where she had mastery. She worked away in our kitchen in the evenings with her soft gummy white erasers and her sharp pencils and oversize presentation boards. My mother certainly knew how to study. She was a lifelong teacher, but more importantly she was a lifelong student. All of this served her well until December.

At the start of the school year, the distance from the States must have restored her confidence in herself after such a turbulent decade navigating her husband’s alcoholism, but she also must have been afraid.

Knowing my mother, she wouldn’t have said it out loud or possibly even been able to name the feeling, but it might have served her well to use the word fear, to let it out and unbottle it earlier. It might have relieved the enormous pressure it was placing on the inside of her body. Or maybe saying, “I am scared” or “that was really scary” was a luxury she felt she didn’t have.

But the hot past would have surfaced at regular intervals now in the back of her mind, whispered to her during lectures or as she studied at our kitchen table, a low-grade overwhelm stirring, accumulating like white smoke around her stool, her feet, drifting about the kitchen floor. You wouldn’t have seen it looking in on her doing her homework. Her features would have masked it as as she erased and penciled and erased. September. October. November.

She would have been revisiting the marriage, anxious about returning home at the end of the year, her fear, languid and smoky, sweeping lazily into the floor of every room but the children’s, my mother kicking through it in the hallways, but still laughing loudly and smiling and greeting friends at the front door, inviting them in.

Because now that she was no longer fighting or fleeing, she had the time to pause and think about what had just happened back there. For sheer horror value, looking back from safety can be worse than living events themselves.

*

We spent the week between Christmas and New Year’s in Switzerland at a family friend’s chalet, where she fell suddenly and violently ill. It was on vacation that she dropped her guard fully at last, and it pounced. The stress caught up with her. She could no longer bottle it up. Ulcerative colitis took her down, and she lost weight and strength precipitously. Her bottle broke.

The brave, vagabond mother with no husband and only the money borrowed from her sister shunted her children home from Switzerland on interminable train rides to Milan and then on to Bergamo. She tried to recover her health in our cold apartment. She moved her bed into the kitchen to be nearer the kerosene stove and the light of the window. There were urgent visits to a doctor in the lower city, possibly a hospital there. It is a blur.

The gravity of my mother’s health was unclear to me at the time. The fact that I didn’t know the severity or wasn’t told remains in a cold corner of my heart where I have packed it away on emotional ice in equal parts injury and gratitude.

Others sensed the stakes. Her classmates rallied around her, looked after her children and maintained warm smiles. They kept her on the team and kept her academic mission alive. Below academic failure for my mother was an abyss that even her children would have been frightened to stare into. So, those classmates knocked at our apartment door, and dropped off class notes, reams of them, from lectures she had missed. They were now her spot on the wall. Their demonstrated love for my mother remains a lesson in fundamental kindness. May they read this.

None of it has been forgotten.

The full serialized text here:

Note:

I’m torn between publishing this all out in one go, my writer’s instinct, or maintaining bite-size, serialized lengths. Even at 1,000 words this stretches a reader’s patience I’m informed by clever bloggers. I would have released today’s entry with Saturday’s in one go, but I’ve bisected it, editing my way to finding the cuts that create intermediate resolutions. I hope this has been reasonably successful.

After Saturday there will two final sections that take the piece to Threshold V. I’ll release those over the next two Saturdays. They are all very much connected to each other, although I’ve had to edit beginnings briefly for those dropping in midway (which pains me not to come in from the beginning, but I’m still very grateful for the visits.)

If you’ve just subscribed, please know that it’s all been very glum for a bit, but this, too, shall pass.

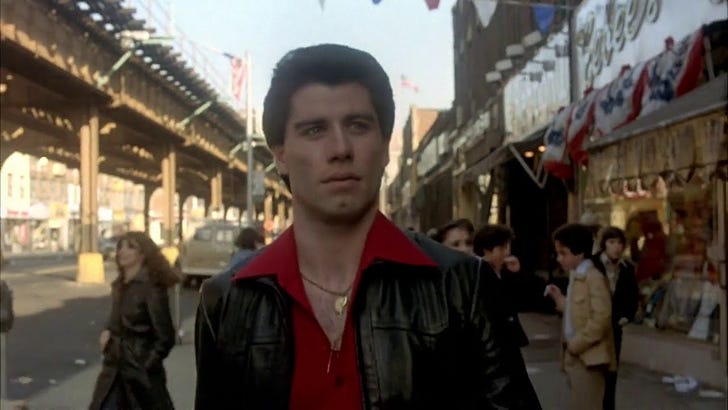

In the meantime, to bring the temperature down (and sharply) here’s a wildly out-of-control description of John Travolta’s opening scene walk in Saturday Night Fever and a light-hearted afternoon from the road on the Camino de Santiago.

Adam

"My mother had been a ballet dancer. When the world started to spin, she knew how to pick a spot on the wall." This gold nugget you unearthed.

Adam, Adam, Adam... Here there be gold.

I feel as though I might lose my mind if all this doesn’t get turned into a film. I so need the image of your Mother sitting above and kicking through white smoke to exist on a screen.

Bless your Mother, what a woman. I so wish I’d been able to meet her.