Iceland, Redux: A Reader's Letter

On Storytelling, Self-Deception, and Laundered Violence

This note was posted in the comments for Iceland, and by the time I finished responding to it, I decided it was a stand-alone post. Joe engages with the story in a way that I wanted to share - and respond to.

Adam,

I’ve read this story several times. I love this story. It’s compelling in a way that I’ve had trouble compartmentalizing. Like a wound I want to pick at. I suppose it’s the universality of it. It’s the mirror you’re holding up that I can’t escape. I can sense you put quite a bit into this, and I’d like to respond with my reading experience. Forgive the length.

First, on the craftsmanship—your characters are wonderfully contemptible. The lot of them. The location and situation provide a great canvas to explore. . .whatever it is you’re exploring. (As you note in your afterwords, once you put it out there, the response is as much about the reader as the author, so what you’re exploring and what I’m exploring may not be concentric circles). It certainly could be mistaken as autobiographical for no other reason than the picture you paint of Iceland and of the relationships has an authenticity that is difficult to fake. Well done.

Here’s my read:

Worse than self-pity is self-contempt, and the former is often a convenient tool to avoid the latter. Philip is no victim and you have a nuanced touch with your telling of his story. Isabella has not made him petty so much as given him pretext to indulge his passive aggressiveness and pettiness. They’re dance partners, not Lord and serf. Philip consents to his ongoing exploitation, ignores his culpability, resents his cowardice, and seeks refuge in victimhood and self-delusion.

There’s great seduction in victimhood. To be a victim is to be denied agency. To lack agency is to be faultless. “I’ve been wronged” is easier to swallow than, “I fucked up.” “Oh look, Isabella is doing yoga,” is easier to swallow than. . .well, you know. . .

I’ve known men like Philip. I suppose I see his reflection in the mirror on occasion. Not that I’ve experienced the slow and then sudden dissolution of a marriage on a polyamorous tryst in Iceland, but that I’ve consented to my own exploitation—if not explicitly then in subtler ways. Small ways. Everyone has. Our light and our darkness are strange bedfellows.

That’s what grips me about this story. You use the crucible of sex and sexuality wonderfully to lay bare (no pun intended) core realities of the human experience and human relationships. We can’t escape the mirror we’re looking into here. We cheat, we coerce and cajole, we manipulate, we ignore painful truths and tell convenient lies. We do all those things to those we love and to ourselves. We volunteer ourselves at the altar of sacrifice so that we may enjoy the power of righteous indignation. We stand on the mantle of courage and integrity only to reveal (with the right recipe) our cowardice.

That each of the characters is contemptible in their own way is obvious but incomplete. I also find them each sympathetic. Walking, talking, living, breathing contradictions just like all of us. There are no good guys (or girls). There are neither heroes nor villains. Life isn’t that clean. We’re just people trying to navigate love, loss, fear, desire, guilt, shame, etc.

It’s not a hopeful story and it makes me sad. I don’t like the characters, and I feel a bit gross observing them so intimately. But it’s as real as it gets. It’s an author tapping into something true and enduring and crafting a story in a way that forces me to sit and stew and revisit and rethink.

And that’s what I love about it.

Thank you for writing it and sharing.

(link to Joe’s Substack at bottom)

***

Joe,

Iceland asks an enormous amount of a reader.

The characters are loathsome.

It’s not funny.

It’s not uplifting.

It’s certainly not sexy.

It’s embarrassing to comment on or share.

It doesn’t label right or wrong.

There’s nothing provided to distance yourself from the conversation you’re having with the narrator. In short, it takes a reader where they don’t want to go. It makes you feel dirty reading it, or possibly dirty. The writer himself might be dirty, or possibly dirty.

It implicates.

So, rough fare. And rough fare for Substack. One minute you’re scrolling through politics you agree with, and the next you’re in Iceland.

*

I ask an enormous amount from my readers.

I don’t lay much out. I don’t label good and bad. I leave half the work to the reader so that the stories can be participatory, whether in a reader’s emotional or moral imagination.

The value I’m trying to provide in 100 Stories is a return on engagement. If I’m successful, and you do re-read or spend time with it, you should find more. If the wine’s any good that month, the wine should open up. If you scan the story in a fast pass, there’s nothing there, or very little, or mere outrage.

The only contract I have with readers is that I intend for them to “Feel something.” Other than that one slippery promise, I offer no contract. Well, that’s not entirely true; I commit to elbow grease and integrity. I do work hard on these stories. My most treasured readers do, too.

Nothing has been more illuminating on Substack than understanding how much of a reader’s experience is created by a reader alone. It’s thrilling. It’s collaborative. It was an unlock.

It’s changed my understanding of what a writer should be trying to accomplish. And it’s changed my sense of obligation of how much I need to spell things out.

Now, I don’t and won’t.

I ask an enormous amount from my collaborators.

*

That said, Iceland:

It is our reader-nature to align with a storyteller’s point-of-view. That’s a knee-jerk sympathy in life and literature. In Iceland, you’re beguiled into being the storyteller’s ally. Then you’re dragged through the rationalized horror of what he’s done, but not copped to. There’s some Humbert Humbert.

If you didn’t get it at first pass, a re-read should reveal the story is a self-described “victim’s” litigation, told through a conveniently hazy memory, with calculated, even compelling, victim-blaming evidence.

Facts, see?

To reread this is to sludge through the moral morass. It’s a crime scene.

Life presents these conversations and challenges our loyalties to storytellers. Life allows us to align with perpetrators out of convenience, out of our susceptibility to their stories, or out of personal histories. Who hasn’t taken the side of a coworker or a friend or a family member over the side of the truth? Who hasn’t told stories?

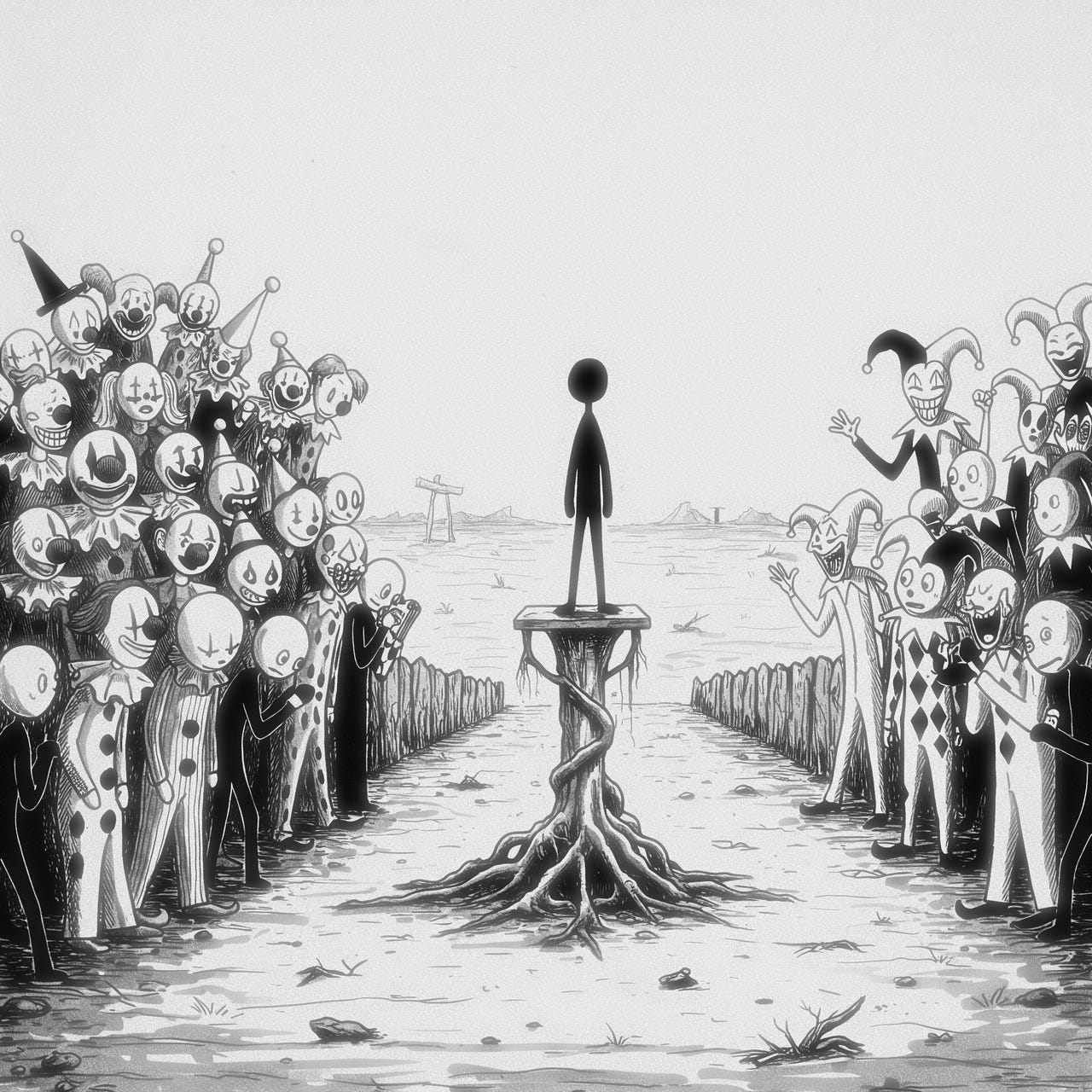

My hope is the reader can’t get away from being implicated by alignment. The point is they aren’t over here and the story is over there. The play is in front of and around them. They are thrust into it, the actors are staring into their faces.

Horrible grease masks.

What to make of it?

You tell me.

*

How much of ourselves do we recognize in these characters and in our experience of hearing the narrator’s story? Isabella and Paolo’s stories leak through, but they are thinly substantiated because they exist as objects in Philip’s story of his victimization. They can’t be entirely real because they are ingredients for something else, although we need to feel them moving in his imagination outside of his interpretation. Hopefully, I did that successfully. I was successful if you started to question the narrator’s claims or were unsettled by them early.

It’s fair to say, though, given the overall dynamic and sustained relationship to Philip that all three are compromised individuals through and through.

Here’s where I hoped to leave the reader stranded:

When you read this story, do you take a moment to ask whether you see any of yourself in Philip, in the reflections of Paolo and Isabella?

Because I think you should. You get at exactly what is intended. We are, in our ways, all human, all prone to seeing ourselves as victims, all capable of grievous harm the closer we are to the bone of our story of being wounded, at some point, somehow, somewhere. We may think we’re here and those characters are there, but I disagree.

We’re not all committing sexual assaults, but it’s too easy to say “that’s not me. that could never be me.” It takes some manning and womanning up to see oneself, even in a reader’s privacy, in these people.

But what’s the value in dragging everyone through all of this?

I was trying to build a mirror. We’re better people when we recognize our darker tendencies and far less dangerous let loose out there in the wild.

Iceland isn’t about sex. Or vulgar, loathsome people. I’ve never been to Iceland. This isn’t a window into my private life, thank God. But like you, Joe, I can look in the mirror and see some Adam in all of them. And that’s the whole point.

So, yes, Joe, as you put it:

“We can’t escape the mirror we’re looking into here. We cheat, we coerce and cajole, we manipulate, we ignore painful truths and tell convenient lies. We do all those things to those we love and to ourselves. We volunteer ourselves at the altar of sacrifice so that we may enjoy the power of righteous indignation. We stand on the mantle of courage and integrity only to reveal (with the right recipe) our cowardice.”

Exactly.

That was the point of Iceland.

Thank you for reading closely and responding so thoughtfully.

Adam

Joe Cole’s Substack

Ok, as a faithful reader, and someone you trust to tell the truth, as I do you, I will tell you mine. Usually, I listen to my favorite Stack people, (you firmly planted within my small but elite circle) when walking through the forest in one of my favorite places. I read on days when just the thought of a favorite post in my mailbox, already has me filled with delightful anticipation.

I admit it, I read Iceland on a sub-ordinary day when reading consisted of not much more than swimming laps when you’re not in the mood.

Thanks to Joe, and your brilliant reply, I will settle in to soft leather, later this afternoon. A warm hearth across from dangling feet. Iceland , on my laptop.

What a treasure box of a letter. Thank you for sharing it. Readers like Joe keep a writer writing.