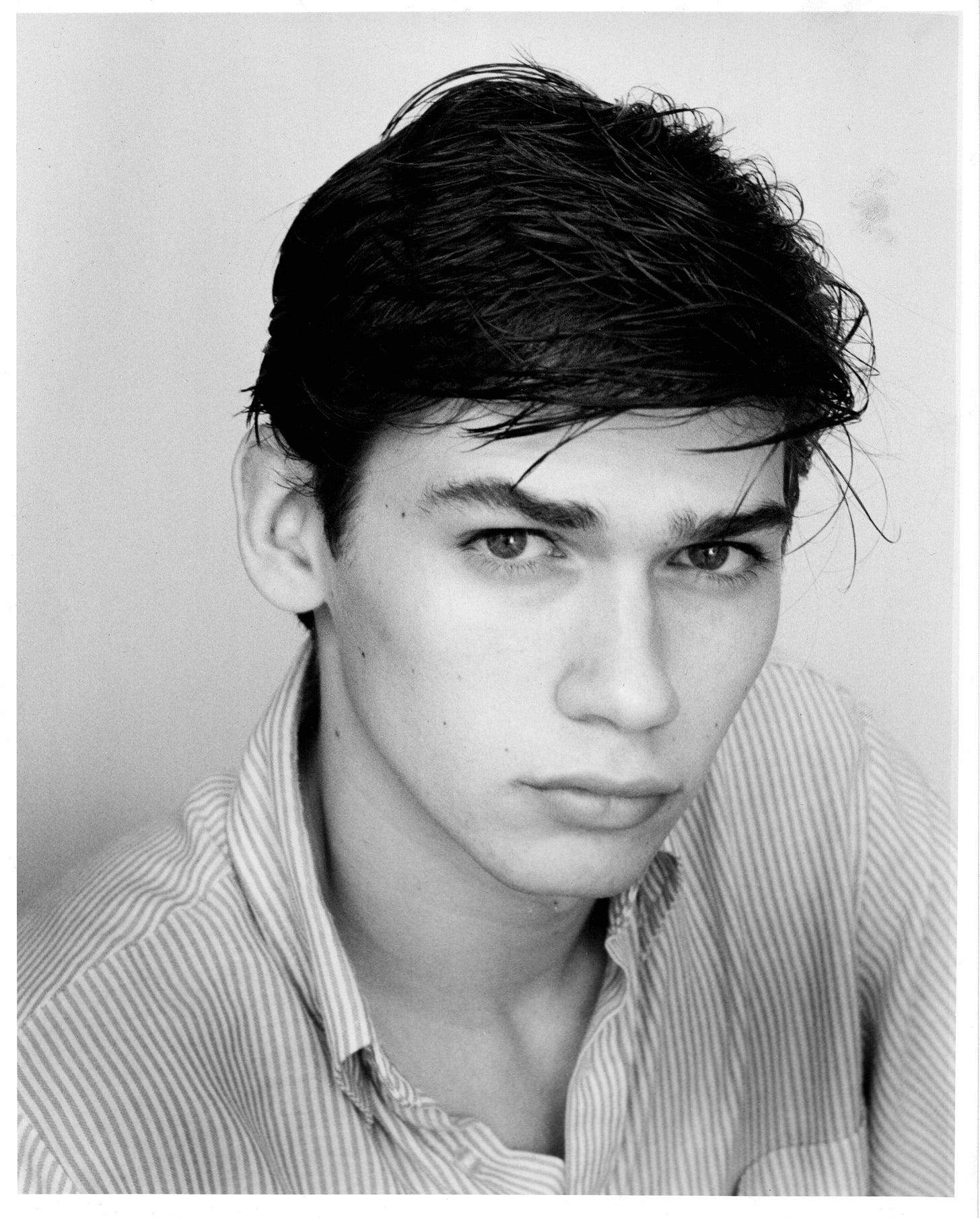

🎬 Actor: The Headshot

My mother and father join me to take my actor's headshot.

My father took the headshot in the bathroom. The photographer’s backdrop was the blank white surface of the shower wall. We put the back porch step stool into the tub so I’d have a chair. We dragged lamps in from another room. By “we” I mean “I.” My father was allowed inside my mother’s apartment to take the picture, but not to roam beyond the DMZ of her kitchen and its adjoining bathroom.

He was not an easygoing man, my father, but this sort of mission brought out something adolescent and playful in him. The task took some of the daring and panache (one of his words) that he admired in others. The son’s audacity with the ten screen test gambit was a validation of himself, particularly as he had been enrolled as a partner-in-crime. This was rare.

Generally speaking, I did not involve my father in any of my activities other than proofing college essays and seeking his blessing on newspaper editorials. There was almost no overlap between us, no shared history or interest in skateboards, electric guitars, rock concerts, or high school girls in back seats. These interests were my lifeblood, but they were alternately mysterious or inconsequential to him.

But the afternoon of the headshot, we had overlap. We were doing something mischievous and cool (one of my words), a word he would have struggled to define, but “cool” must have been what he felt pulling the cardboard top off the box of headshots a few weeks later.

He felt what I felt that day at the printer’s. I know he did. He was, at the end of the day, my father.

*

My mother was not in the bathroom as a co-conspirator, but she would have been within eyeshot of the bathroom door.

The layout of the home is relevant. Our apartment was on the first floor. After the divorce of my parents, my mother purchased the home with her inheritance, and she rented out the second floor to maintain the mortgage. By the afternoon of my headshot, my parents were long since divorced, but they were reliably on and reliably off in a sine wave of platonic relations. That afternoon, they must have been at full moon in the waning and waxing, otherwise the son and his father would not have been crowding lamps into the bathroom or back porch stools into the bathtub.

But waning or waxing, there stood an invisible wall between the kitchen and the rest of my mother’s home, a barrier my father was never allowed to breach. The cost of defending her financial and psychic walls led to the ulcerative colitis that staggered her at regular intervals before it took her life twenty years later, but my mother could compartmentalize people, ideas and time. You may laugh at my kitchen table, Barry, but not within my living room.

Their on-phases were a respite: Saturday morning badinage at the kitchen table, my father arriving to pick up his children, parked where he was allowed in the back driveway, my mother’s loud laughter fueled by attention from Barry, my father’s chuffed calm, trousers (his word) casually crossed, his settling backwards an extra degree, the slowed tapping of his Chesterfields.

His voice changed when he was comfortable, when he was the center of attention, holding court. It found a burr, a purr, something sophisticated and unusual that my mother must have adored in their early years. The two of them could banter with each other more intensely than with anyone else in their too-brief lives. Neither backed off their opinions for each other, not a hair, and agreeing or disagreeing, they had the benefit of a marital shorthand, and they had shared interests and references and intellectual gifts. They had overlap.

They were moons sharing the gravity of some dim planet. And when my father lay dying from cancer a decade later, my mother moved from Oakland to Minneapolis to care for him — and, still the two waned and waxed. The same flashpoint battles and platonic truces broke out again, this time in the DMZ of my brother’s home. They laughed, they stormed in, they stormed out, and then they conversed for hours on his deathbed, my father beneath the sheets, my mother above.

And sometimes, quietly, the two of them sat side by side and read.

*

In the last year or so before the fallout of their marriage, and over a decade prior to the afternoon of my headshot, my father became an avid photographer for a season.

Even as a six-year-old I knew that my father owned a “Nikon,” something best-in-class, something rare, a marvel of mass and green glass and rotating knobs and latched chambers that I was too young to be trusted to hold. (Even with the strap draped carefully over my head, even then my father held the camera for his younger son — if not from him.)

But I was invited to peer through the porthole eye rubber to look into his precision world. And even if I didn’t understand what I was being told about Nikon lenses, when the camera was angled right for the fleet sighting, I saw something marvelous in there that was very much my father: twitching black levers with hollowed circles, intelligent decimals, something sandy, matted and dim on the canvas of that miniature screen. In that crisp darkness, I could see the mechanical, pristine elegance inside my father.

Awe. He was showing me Awe. This he did understand about fathers and sons.

Other than the actor’s headshot he took on this afternoon many years later, though, I can’t recall a single other photograph of his. Photographs weren’t the point.

*

My mother sitting in the DMZ outside the bathroom on the day of the headshot would have had time to think — and too much of it. She would have remembered my father’s earlier pictures. Two of them in particular.

These were not the first headshots my father had taken of his children. He had taken passport pictures of my brother and me — in secret — directly before the collapse of their marriage. We were six and eight. Scotland, I believe, would have been the destination. For that photo shoot, the white living room wall must have been the backdrop. In the end, those two headshots were never used. My father had the daring to take the two pictures, but he lacked the courage for the deed.

For my father’s sake, I wish he’d gone and done it. His life needed one wild act of pure bravery.

Let it be a kidnapping.

*

(Oh, how my mother would have howled with good-natured laughter at the image of Barry kidnapping anyone. My father at that kitchen table would have closed his eyes, shaken his head, and, bemused, pretended not to understand.)

*

As for my mother sitting tight-lipped in the kitchen during the photo session — she would not have been supportive of the fraternity mischief playing out in her bathroom. Whatever this male thing was, it threatened the handhold-by-handhold achievement by academic certificates that she trusted and had benefited from. A bathroom headshot and a fake acting resume were cheating to her, anathema. Acting in movies should follow years of acting on the stage and training and study and, inevitably, reading.

My mother herself was at times spectacularly courageous, but she was not the joyful possibility that shines through in acts of daring. There’s a difference between courage and daring, and my parents lived across that gulf. My father dared to take the pictures when she was out one afternoon. My mother had the courage to steal the children off to Italy with no money and no husband.

Later on, after my own daring had paid off, I could see that my mother loved my work in film and, in spite of herself, deeply admired her son’s chutzpah (her word). Undoubtedly, this was possible because she was no longer afraid for me.

*

And yet, Adam… and yet…

My mother was in the bathroom photography studio. My mother was the parent that loved the movies.

She would spend her last five dollars to sneak out and see a foreign film with me. We would rummage and pilfer from our separate coin jars as accomplices. She’d pencil out IOUs until Friday’s paycheck to pull off a trip to the movies. The rides to the foreign film theater, miles and miles away, with the radio blaring or the two of us swept away in conversation, were our mischievous joy. We had overlap, my mother and I, and a great deal of it.

In these films my mother loved, there were no dreams too far. She would have wept with delight for a character with her son’s audacity and, later, with her same unbridled movie theater heart, she would have cheered that character’s courage when he pressed on in his accidental career.

In the darkness of a movie theater, it was safe for her to pretend and to weep with delight for proxies of the ones she loved. Actors were her People, and in the iridescence of movie light my mother freed her hummingbird soul.

*

To understand what happened to my acting career, simply know that I carried the one, the other, or the both of them into every audition, and from every director’s cry of “Action” to every “And Cut.” The two of them ran wild in my psyche, ranging room to room in the red bloom of argument, waning and waxing, castigating each other in marital acrimony, but, also, at times certainly, leaning back at ease in the kitchen wiping tears of laughter from their eyes.

I had my successes, significant ones, but when I failed, I felt the gravity of their moons. I was tugged by my father’s “I can’t do it” and my mother’s “you shouldn’t try.”

Both of my parents would have had it otherwise and wept to read this, but they were not coaches for a dream team that came in first, and I was not a dream team player.

We didn’t act, and we didn’t play.

Crickets,

I was sick much of this week with the Virus-That-Shall-Not-Be-Named. 3x!!!! Huge drag. I’m behind on everything. Today was supposed to be the second of three parts of Threshold. That wasn’t ready to come out of the oven. I’m still not satisfied with tiny tweaky edits, but I’ll post it next Saturday. This piece also blew through the “1000-word” word count ceiling I committed to maintaining for Wednesdays. Whose bright idea was the word count?

On Thursday, the 12th, this newsletter will celebrate its one-year anniversary. It will be a quiet celebration for friends, invitations by email, and a quick look back at the 5 posts that I would keep if ordered to get rid of them one by one. Some of you know this is a theme with me. I’m always closest to the piece I’ve just published, and faithless to the rest, so don’t be surprised if this piece makes the short list.

Lastly, inquiring minds, why “Crickets?” The lighter answer is that it is a micro-complaint about not having more comments after some of these pieces — when all I hear are “crickets” — even though I see the page view counts.

But the true answer requires a tiny bit of imagination on your part.

Imagine standing in a summer field at night, closing your eyes and hearing nothing but the chirping of thousands of crickets. That’s what it is, for me, possibly for any writer, to put one’s work out into the world and to be heard by their readers. (A writer needs only a single cricket to press on. I know this to be true.)

And for those of you who do leave me comments or engage with others, well, cup runneth over, you’re my Fireflies Maybe it should be Crickets & Fireflies.

Hmmm. Hmmm.

Hmmm.

Hmmm. Hmmm. Hmmm. Hmmm.

A.

I like to think of myself more as 'grasshopper' than cricket, though your point is taken. Many of my best memories are filled with the songs of crickets, sounds of fullness and life, on and on through the lonely hours, not emptiness and expectation of something better, something that isn't crickets that one hopes will arrive. Your storytelling is so tight and confident, so personal that commentary almost seems intrusive and beside the point, but then I'm pretty sure, given your keen awareness you already get that on some level. You've worked hard to polish and refine the exposed marrow and bones to the point that criticisms would, in many cases seem superfluous, just some ego trying to have something important sounding to say. The headshot story itself fleshed out so many other, earlier-told stories, answered small questions that had been hanging there in the air, unrecognized, unasked. I came away with glimpses of three wonderfully flawed souls, each feeling their way along a series of dark and light passages, looking for and loyal to connections, however tenuous, and in the end, quite liked each one of them because of, and in spite of their quirks, scars and failings. One of my favorites, thus far, sir. Thank you.

May your cup runneth over. We writers must connect and the vulnerable and often "unsayable" connect us through emotional truth ... and comments that show the reader has read, understood, related or objected ... to Adam Nathan, actor, author, speaker ...