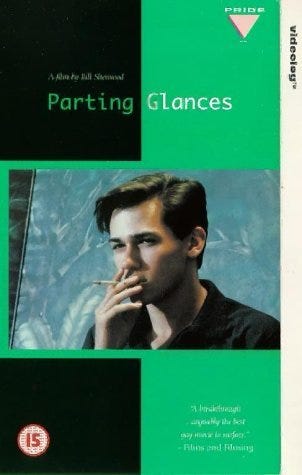

🎬 Actor – Parting Glances

Fight, fight, fight, fight. A few thoughts on my role in Parting Glances, its actors and filmmakers, the health crisis that spawned it, and the relentlessly uncertain future of gay men and women.

It couldn’t have been a smaller part, a few lines at best.

I was offered the role of one of three townie teenagers harassing Steve Buscemi’s character out on Fire Island. The film was Parting Glances. Steve Buscemi wasn’t even “Steve Buscemi” then — although he would be after the film came out with rave reviews for his performance. If there were parting glances for anyone in this film, they were from Steve looking back at his career as a NYC fireman.

As I had with Amateur Hour, I found the casting notice through Back Stage magazine and submitted a headshot. It was my second audition and again, incredibly, another bite. (I was still in the early days of beginner’s luck. You can’t imagine how easy I thought all this was.)

The filmmakers were ambitious: it would be the first film touching on the AIDS epidemic, a real film I was assured, not some kind of other film I might regret being associated with for the rest of my life.

There was a lot to consider. In 1984 when this was casting you could still count on two hands dramatic films exclusively about gay leads. Hollywood films spoke in code and films about gay characters were rare. Films about gay characters not tormented about being gay were even rarer.

And there was more: Auditions through Back Stage were a mixed bag. Imagine Craig’s List for actors. I had no script and zero idea what I’d be getting into. There were only a handful of lines. The part carried some level of professional and personal risk. I was a straight eighteen-year-old who wanted desperately to be cool. You can’t bring #2024 to this.

This certainly wasn’t a film to be cool in. On the other hand, Bill Sherwood, the film’s director, struck me as the real deal. I trusted him instinctively. I trusted the producer. And I was sympathetic to Bill’s vision for the film.

But I made my decision.

In my beginner’s luck imagination I was already much too important an actor to say yes to any part that had a pound sign after it. Parting Glances presented nothing but risk. The film would never come out, and anyway look how easy landing a movie part was.

You get every one you go up for.

I turned down Townie #3.

*

That I ended up in the film was a fluke.

At some point prior to the start of principal photography on Amateur Hour I ran into Yoram Mandel, Parting Glance’s producer, on a street somewhere on the West Side. We remembered each other from the audition. He’d heard I’d won the lead in Amateur Hour, congratulated me, and then told me a much larger part was now available in Parting Glances.

Apparently, they’d let the original actor for this larger role go. Mandel practically offered me the role on the spot.1 I hadn’t been recorded on a single frame of 16mm film yet, and look, I was already important! Cast in the street! I felt flattered, in demand, ascendant, famous! Oh, these early Midas Days that teased and then deserted me!

The newly tendered role was Peter, a gay college kid, romantically interested in Michael, Richard Ganoung, one of the leads in the film. Peter was romantically circling, waiting for an opportunity to strike when the lead’s boyfriend moved away for a year on a job transfer. It was a significant part Yoram explained — and it was. The part would later end up fourth in the credits.

“Bill will call you,” the producer promised me.

I met Bill in his Upper West Side apartment to talk through the part. He shared the script. There were scenes throughout: in a record store, at a party, on a stairwell, alone in the final shot of the movie knocking on Michael’s apartment door.2 I was leaning in towards a yes now.

I double checked more directly on whether I’d be touching, kissing, hugging, holding hands with anybody, brushing against them in the hallway accidentally or otherwise. I didn’t want to. I was frightened to. I had no idea of the potential repercussions. God knows what else I was worried about. I think I asked that this guarantee was in my contract. (I know. I know. I know.)

Bill assured me — again — I wouldn’t be. The closet was packed in those days, and here I wasn’t even gay! I was coming out of a closet I wasn’t even in! What the hell was I doing? Nobody really believes actors aren’t who they play. That’s half the fun making the one the other.

And — also, let’s get real — my concerns were legitimate, particularly for a budding teenage actor. Typecasting was a much bigger deal in those days. To play a gay character might be a road to playing only gay characters. Forever. Gay part, gay part, gay part until was acting in plays in a nursing home. The level of stigma around being gay was through the roof. (Even my agents later counseled against any other gay part of which there were suddenly offers. I wasn’t alone in evaluating the risk.)

Bill assured me, slowly and clearly — again, dealing with Mr. Cool Eighteen-year-old — that I wouldn’t have to “do” anything. My god, he was patient with me. When I turned away, he must have rolled his eyes and banged his forehead.

Hey, #2024, let it go. You have no idea. You weren’t there. It was different. Your generation has boys that are high school prom queens. Unfathomable.

But I also wasn’t a bigot, and I didn’t want to be numbered among them then or now, and I understood the movie was about foundational dignity. I went to college in New York City to be closer to all of this, to be near better, braver people, to fight for civil rights, for dignity. To run would have been moral cowardice. That felt like a line you can’t uncross. And here I was.

“I’ll do it.”

*

Parting Glances was a success out of the gate, initially with the gay community and then expanding immediately to a far broader audience. The film struck a nerve. Gay men — and gay women — walked a little taller coming out of the theater. It played for what felt like ages at Embassy 72nd Street opposite My Beautiful Launderette, the Embassy one of the three major art house theaters on the Upper West Side. Possibly later at the Angelika. To see posters for my film at the front of a theater that I went to regularly was a life milestone. To see people lining up on the street at the Embassy was surreal. To have people approach me on the sidewalk and tell me how much they loved the film was incredible really. This went on for years.

There were other milestones, uglier ones. The reception on the street wasn’t always warm. These were the early days of AIDS and “the gays deserve it.” And the key word in those quotation marks was reserved for polite company.

A guy in a bodega in the Village came up to me once and told me with seething contempt that I was in a “freak show.” “Why are you in that freak show?” The words were burned into me. And that was just one guy who was miserable enough to approach me. If I hadn’t been scared of him, I would have asked him why he went and saw the film in the first place, but striking so close to a nerve would have been dangerous. I hope he knows that it’s safe to come out now.

That miserable encounter was a taste of the thing I despised and believed New York City would be better than. It was the briefest glimpse through a window into the contempt gay people have to put up with.

That encounter only made me prouder to be in the “freak show.” It raised some dormant defiance. Fuck him. Fuck all of those people.

And fuck all of you now.

*

For years Parting Glances remained on Top 10 lists for gay films. More recently it’s been crowded out in these lists by big budget mainstream films with exotic locations and movie stars that a little indie film financed scene by scene couldn’t possibly compete with. At one point I was gifted a great coffee table encyclopedia of 20th Century film and Parting Glances was in there for the year 1986, another milestone. The gift giver didn’t even know it was in there. They knew I loved the movies.

Parting Glances launched more than Steve Buscemi’s career. Kathy Kinney emerged from it to become a television star on The Drew Carey Show. John Bolger worked for six years on General Hospital and a number of commercial films and more recently The Only Living Boy in New York. I had my own more modest successes afterwards. They were smaller, but they were genuine.

All of us have Parting Glances and Bill Sherwood to thank for that.

*

Strategically, Parting Glances wasn’t selling a “we’re here and we’re queer” message. It wasn’t a clarion call. It wasn’t strident. It certainly wasn’t ACT UP. I stated more simply “Yes, we’re here. This is us. We’re not a freak show actually.” For some viewers maybe there wasn’t enough “here and queer.” I’ve heard complaints about the film that the gay community represented in the film was “straightwashed.”

Possibly.

None of the major characters were “flamboyant” or whatever word captures the thing you know I’m getting at here, and three of the top four male roles were played by straight men. In many ways the vibe was wealthy Manhattanite yuppie with Steve’s role a rock and roll star, a different direction altogether.

Incidental characters were undeniably gay, “types,” and they add a great deal of atmospheric color to the film. In my take on Parting Glances, Bill was saying, insisting really, “We’re here. We’re living complex lives with complicated, tender, committed romantic relationships, beloved friends, sophisticated music, and, you know, fuck it all, laughter.”

That and “oh, we’re dying.”

Janet Maslin in a lukewarm and largely sniping review made a point of this in the New York Times. I know the review upset Bill. He must have wanted a warmer welcome in his home town. Maslin was kind to my performance, if fleetingly, and she made a generous concession to Bill’s overall handling of AIDS. The review was better than it could have been, but there were good reviews aplenty elsewhere.

The Washington Post got it spot on.

More recently, Lit Hub is very generous with its assessment of the film and my own performance.

Quentin Tarantino all in on Steve Buscemi in Parting Glances. It was the catalyst for Buscemi’s role as “Mr. Pink” in Reservoir Dogs.

“It is to both his (Steve Buscemi) and the film's credit that the anguish of AIDS is presented as part of a larger social fabric, understood in context, and never in a maudlin light.”

– Janet Maslin, New York Times

*

In the early 1980’s, our President wouldn’t acknowledge the AIDS epidemic existed. Not a peep. This reluctance coming from a former actor no less. Shame, shame, shame on Ronald and Nancy Reagan. Think of the gay actors he represented as the head of the Screen Actor’s Guild only a few years prior — many of whom were undoubtedly close friends. Talk about double lives. But to surrender to his prejudices or his constituencies or both, there was no federal funding in the fight against AIDS until 1986 the year Parting Glances is released. Think of what we’ve just been through, and this is incomprehensible.

The death toll was staggering. It’s drifted too far from the popular imagination. By the advent of the antiviral cocktail drugs in 1995, I’d lost my agent, my manager, three friends at a single restaurant I worked with in Beverly Hills, and who knows how many others in my close orbit died that I never heard about.

These were people I cared deeply about or simply knew or worked with and divided tips with and shared drinks after work, and laughed at funny impressions and double-dated, or acted with in films, or went to their plays. They slipped away often privately, emaciated, lesioned, of course terrified, and far too often in shuttered silence.

It was ghastly. I don’t have a better word for it.

*

Two of the many deaths that will haunt me forever were taken from the young. Teenagers. There was Frankie who made the espressos in the back at that Beverly Hills restaurant. He was about the sweetest, gentlest kid in the whole world. How else to put it but “everybody loved Frankie?” Everybody. He couldn’t have been twenty when he died. Jesus Christ. RIP Frankie. In my mind’s eye I can see your face even now.

And another kid: a kid I never even met, a voice. I heard him for a minute or two. He was a high schooler who called into one of those Love Line shows on the radio. He explained he had sex one time with a guy at his high school. It was the first time he’d ever had sex and he contracted HIV. The kid said, “I don’t even think I’m gay.” It was “one time” he repeated until I wanted to crack. Every listener in the Tri-State Area must have felt the same. He couldn’t get his mind around it. The “one time” was somehow a key to making it end, but the key opened nothing.

This boy wept on the phone, and the radio host had nothing to comfort him with.

That was AIDS. It was a riptide.

“Still, Sherwood offers an intelligent alternative, sure to be a welcome relief to gay men who are sick of TV movies about getting AIDS or telling the family the awful news. Here there is nothing particularly odd about gayness. The youngest character, a record store clerk, told his folks when he was 16. He wants a normal life, he says, "a co-op on Central Park, a BMW, a house in Bucks County.”

— Rita Kempley, The Washington Post

*

And then Bill died, too.

He hadn’t contracted HIV when he created the film, and he never got to make film #2. The last time I saw him he paid me the last of my deferred payment for my role in the film. (This was its own saintly act. Nobody bothered with deferred payments for actors in indie films. That the film was released was your payment.)

Bill also gave me a manila envelope with clipped reviews for everywhere I was mentioned. He’d cut them out and saved them for me. I’m sure I must have thanked him, but I was far too self-absorbed to appreciate his generosity at the time.

The two of us were standing on Broadway somewhere in the 80s, outside a Chemical Bank. He was telling me about his next script, something about a classical composer maybe. He was struggling to get funded, deeply disappointed, but memory may be failing me here.

And then he was swept away, too.

*

Several of the locations we shot in must have been in apartment buildings of friends of Bill’s. Costume and wardrobe changes were conducted in cordoned- off bedrooms. Some of the decor, paintings, sculpture were, at times, eye-poppingly “Agador Sparticus," and I would not have been surprised to see men playing leapfrog on the Birdcage china. This was not a world I knew or fit into.

I was a stranger in a strange land.

And the male power dynamics were different than anything I’d ever been part of. By today’s standards, at least some of the interactions were solidly #metoo, the teasing sometimes condescending and occasionally crass. All of this a sexual dynamic I didn’t understand or know how to manage artfully. But, all of us had thicker skin then, and honestly, it was the furthest thing from traumatic. It didn’t seem to have anything to do with me. Not really. This might have been fueled by my age and pretty boy role in the film, or it might have been fueled by me turning out to be straight. An imposter? Or it might have just been Me. Probably Just Me.

Or I could be wrong about all of it.

The scene was foreign to me. I was never at home on the set, but then it wasn’t my home. If I had been gay, good Lord, I would have been in a small and remarkable heaven. It would have had me sending breathless letters back home to some secret friend in Kansas. “You have to move to New York! Oh my god! Saturday! The sculpture in this guy’s apartment!” For some rural escapee, the community would have offered a rare pocket of security and freedom, an oasis, a lifeline.

I was taking up space there. I know I seemed aloof to many, including one of the stars who shared his criticisms of me publicly — and hurtfully. I believe he read me incorrectly and unfairly.

*

Anything resembling homosexuality that I previously had any visibility to was different, distant from my world, a few friends or acquaintances of my parents, the odd, suspected teacher, the odd, suspected movie star, Elton John! The Village People! Poets!

You laugh, #2024, but you’re as ignorant now of all of this as I was then.

I knew people that were gay, of course, but I was innocent enough not to think any of my own direct peers were actually gay (ha ha ha ha, oh yes they were, Adam). I only believed someone my age was gay if they were obviously gay, flamboyantly and bravely so.

Not a single one of my classmates at an all boys boarding school was out. Not one. What were the odds? A statistical miracle! If a classmate was called a f— I assumed it was to be hurtful, a cheap shot, not to be targeting something hidden that could be called out and shamed. It is so jaw-droppingly naive now.

The visibly homosexual in New York City were another matter entirely: gay men cruised the Village, ranged the piers on the Hudson, covertly snuck into front of bars with blacked-out windows and anvil-clanging, eye-popping names. Being openly gay was an act of courage and Rubicon Commitment, risk and repercussions. None of this is news, Officer, but I’d like it on the record.

Those repercussions could be ugly indeed. In the late 80’s a demonstrably “out” co-worker at an art gallery had the shit kicked out of him coming out of a gay bar in West Hollywood. I’d never seen anything like it. His face smashed in, a swollen over eye with great weltering bruises.

There was just “why?” and grief.

*

In New York City now there are a lot of references to the exceptional time that the 1980s were. There is an expanding mythology around the decade: exhibits in museums, videos of Madonna dancing at the Limelight, CBGBs, pictures of Keith Haring spray painting in the subways, rap artists and break dancers spinning on flattened cardboard, all of this long before their boom-box sounds emerged as rap and then, finally, morphed into world-changing hip-hop.

When I hear enamored praise for the resurrected decade now, it surprises me, like the artists and journalists now are talking about some other gilded place and time than the one I lived through. It didn’t seem all that special at the time, but it turns out it was apparently, and slotting neatly into that time and ethos was the movie Parting Glances. Now this I did know. The film — my film — played its part in the decade’s New York mosaic.

The young perpetually criticize previous generations for doing nothing, accusing them of letting the world collapse and kicking their cans into the future. And point taken. They aren’t entirely mistaken, but while we still had the energy to, my generation did accomplish something, gays and straights both and together. We notched a win. Gay people now marry each other, protect their relationships in the eyes of the law. They have their love legitimized through the courts. They can visit each other on their death beds. They share their health insurance and bequeath their inheritances. Again, Officer, write this down so I can sign it somewhere. I want this on my record.

Relevant to all of this, and without a flinch, straight men — major movie stars! — now appear as gay men in films with only the yawn-inducing backlash from the usual quarters and pulpits.

I see women walking hand in hand through the park and men kissing hello in my Brooklyn neighborhood — on the lips no less. They look like attorneys. And I barely think twice about it now.

No.

Stop.

This is not true: I still think about every single time, and I know what made it possible, and I know how precarious it all is, and I’m not sure you know, #2024.

Parting Glances is a brick in the structure that supports this. And you can find my own signature on that brick. It's small, but it’s there, distinct. I wasn't at the front line of anything, but I marched and I signed and I gave and I acted and I lent my mass to that crowd and then that crowd broke through onto the steps of the Supreme Court.

Yes, I was a stranger in a strange land, but you can find me in the Obergefell Choir in Parting Glances. You don’t even need to look all that closely.

*

But you should not be fooled, #2024.

Grim history has made it very clear that this is not a permanent state of affairs. Ours is a beautiful intermission, a respite, a pre-battle belle époque.

Fight, fight, fight, fight to hang on to it, gays and straights both. Your Rainbow Generation is beginning to move on. Give them a nod and a parting glance.

I might be getting a 1000 things wrong in this, let me know gently, and I’ll correct them.

As simple as knocking on a door was, I couldn’t get it right, and it did not make the final cut.

Gorgeous. gorgeous. gorgeous. All of it. The way you so honestly describe your internal process when you're considering whether to risk being typecast as gay, without making excuses, and the way you didn't know what it would be like to later succeed in acting. The way you keep reminding us not to judge the milieu of this story by our 2024 standards (and I needed that). The way you cringe at your teenage self's probable lack of appropriate gratitude when you saw the director for the final time (and oh, I felt that).

I don't know how exactly you evoked it, but I saw and smelled and heard New York from visits made in my teenage years in the early 90s, when it was so much more colorful, and sharp, with lots of black shadows for contrast, and without all the sanitized, slick, glassy white surfaces of today. The grime and energy of it. How you reminded us Gen Xers what changes we pushed for. How things are materially better for folx now, though of course we still have a long ways to go. So good.

Wonderful writing! You should write a book.