🎬 Actor – Full Text

An episodic memoir of twelve years in film.

Chapter 1 – The Bet

“I’ll bet you a $100 I can get into a movie in ten screen tests.”

It was the summer after my Freshman year at Columbia. I rented a room in a fraternity on 113th Street, a few blocks south of campus. For $150 a month I didn’t have to return home, possibly, hopefully, ever again. I was addicted to New York City. Leaving the city was like holding your breath and diving.

My room that summer was a space crafted out of a larger bedroom from two-by-fours and shoddy drywall. It had ten-foot Victorian drapes repurposed for a doorway. I thumbtacked Keith Haring and a Last Waltz movie poster onto the walls. I kept a shoebox stuffed with high school love letters and oversized Valentine’s cards. I had a Bible that hadn’t been opened in nine months and a three-ring binder of Freshman Comp essays savaged in red pen and triple question marks.

The fraternity had been coopted by transfer students. None of them cared about fraternities in the least. They did only enough to keep the charter active and the university housing department at bay.

Two of my fraternity mates spoke multiple Asian languages. Another, a hard-core conservative and member of the debate team, had already been published in a political journal, another chained Dodge Hall shut and gave anti-Apartheid speeches on the steps with a megaphone. I admired all of them. They were exactly who I’d hoped to meet at Columbia.

The guys were slyly caring. They allowed a destitute former grad student who’d suffered a brain injury to hang out in the front room with his dog Shep and the physics books he still carted around. In that same front room we played ping ping on an uneven table by the huge fireplace. We yelled up the stairs when calls came through on the basement stairs pay phone. We scribbled phone numbers on the bare plaster.

Visiting girlfriends made a point of not sitting on the dirty, broken couches, and they laughed with their friends about not touching anything in the building — anything, that is, besides bare pillows and the sheets coming free from their boyfriends’ mattresses.

We grinned in our beds when jokesters called out to keep it down up there, and the stairwell exploded with pent-up laughter.

*

By the end of my first year, the faintest outlines of a professional future had begun to emerge in mental sketches of maybes and erasures. I played electric guitar obsessively. Maybe I’d be a musician. I’d been the editor of my high school newspaper. Maybe I’d be a journalist. I majored in Russian Language & Literature. Maybe I’d be a journalist in Russia playing electric guitar with my embassy comrades. I wasn’t exceptional in any of my interests, but I was competent in each of them.

And if I hadn’t read the scandalously intrusive contract for working for the NSA on a frat brother’s desk, I might have become a spy, but a spy in a friendly way, like an in From Russia With Love way, in it for the mysterious, wary girls with the high cheekbones.

That hot summer, doors spilled open onto everything.

*

The $100 bet didn’t come out nowhere.

A friend and I had been on the steps of Low Library when he pointed out a student walking past us. The guy was starring in a movie called Gremlins. This was mind-blowing to me. That a college student could be in a movie was as farfetched as a classmate being an astronaut.

An Italian girlfriend had her hand in the bet. A few weeks prior, I’d sat down next her in a McDonald’s on 69th street and Broadway, and she surrendered to the chatter and agreed to go out with me. She was moving back to Rome to live with her mother. The two of us hung out endlessly as that romantic clock wound down.

We were in Midtown at midnight, making out in the quiet of a skyscraper’s public garden. She had seen Gremlins, and she promised me I was better looking than my classmate. “Good looking” was my only known criteria for being in a movie. She squeezed my mouth together with the tips of her fingers, shook my head back and forth, and said you’re so pretty, Adam. With a flap of her Italian butterfly wings she changed the next decade of my life.

So while my freshman year roommate sat on one of the dilapidated, sunken couches in the frat common room, I threw the $100 bet out there.

“Ten screen tests.”

He took my bet. We sealed it with a handshake and a laugh. He didn’t even want to win. He’d bought into the bravado. He was happy to lose for the adventure of being close to such an outrageous outcome.

I’d never been on a stage. I had no resume. I had no headshot. I didn’t know there hadn’t been screen tests since the 1950’s.

But I won the bet.

Yesterday, when I texted my friend, he no longer remembered any of this. Nothing.

*

Forty years on, I’m taking stock of what I won — and lost — in the twelve rollercoaster years that followed that handshake.

Oddly enough, writing this preface, I’m aware for the first time of how much I lost – the loss started immediately – of everything I’ve shared above, right down to the teenage bravado.

More than aware. Concerned even. Surprised by the surfacing regret.

Regret isn’t at all what I planned writing about. I imagined a few tidy essays on my time in the movies.

Chapter II – A Christmas Carol

Ignore everything Adam is telling you. It is simply not true that Adam never acted before. He was twelve. He was in the sixth grade. I was there.

His roots were humble, but he was a child comedian and actor of local renown. A young fan could catch his daily 9:00 AM and 3:00 PM stand-up performances in Ms. Crosby's homeroom, but he reserved his edgiest, most irreverent comedic work for music and art classes Tuesdays and Thursdays. For pathos and hysterical weeping, on the other hand, you could find him directly after those classes in the vice principal's office. The waiting area in the school office was his green room.

His stand up was well-received, but he had a formidable competitor. Ms. Crosby, his homeroom teacher, and our future star were in a veritable comedy slam. In different ways, neither of them had the slightest self-control. When there was even a smidgeon of a disruptive comment to contribute, Adam did not miss the occasion. Ms. Crosby, for her part, made the astonishing choice – even for that lawless era – of pronouncing the boy's name Adum.

Her genius was subtlety. You had to listen for it. A-Dumb. She knew how to work the crowd with it, too. The interplay was like watching two comedic masters at work. The class hardly knew who to root for. As for the teacher and student, the two of them found each other so outrageous it would bring tears to their eyes at the dinner table.

"She told the whole class that I was 16th percentile in listening comprehension!"

Meanwhile, at the Crosbys’:

"Oh, honey, I could kill the little fucker.”

*

But it was his star turn in a theatrical production of A Christmas Carol that I'd like to “Exhibit-A,” as it were.

I'll set the scene.

The basement stage was in a cafeteria fifteen yards from the lunch-time concession stand where students purchased half-pint cartons of milk for $.04, chocolate milk for $.05, and ice cream sandwiches for $.10. Young cashiers with sufficient math skills to make change for a nickel spilled coins everywhere, pennies rolling decade after decade under the radiator.

During lunch a teacher's aide, Mrs. Somebody-or-Other, stalked the room for oranges to peel, flipped open Partridge Family and Adam-12 lunchboxes without permission, and poked into paper bags looking for fruit. She was proud of her peeler, corkscrewing great ribbons of thick-skinned oranges onto lunch tables.

Adam was sent to school daily with exactly four cents, a paper lunch bag, and a rindless juice orange that was impossible to either slice or peel. It's hard to believe that four pennies, an orange, and a paper sack could create so much shame in a child, but Adam was able to mine it for his performances in the vice-principal's office.

*

Adam played the role of Scrooge in the production. He entered stage right from the hallway across from the janitor's office wearing a bedsheet nightgown and a girl’s white pom-pom winter hat.

In a Dickensian plot twist, Adam didn't just memorize his lines. He was so far off book he knew everybody else’s lines, too. “Adam Lurndhizlines,” Dickens might have called him. This was a good thing because the rest of the cast continually lost their place in the playbooks. As a result, the audience traveled back and forth in time from Act to Act and Christmas to Christmas.

In his alternative interpretation, our Scrooge did not, in fact, soften his heart after the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. Instead, he doubled down on the Scroogery, passed from fully “off-book” and then headfirst into “off-play,” crashing through the fourth wall, before prowling out into the audience.

He barked out, “And? And?” first yelling at the Ghosts, and then at the terrified Cratchitt family at their dinner table, and, not one to mince words, went after the audience directly.

*

Ms. Crosby, who fancied herself a thespian in her own right, assigned herself the role of Bob Cratchitt. She darkly anticipated the groveling of the class clown in the third act. This child owed her an apology, and she was going to force it out of him through cunning.

That was a miscalculation. Her young charge was, at last, in his element. In the spirit of Scroogean Comeuppance, A-Dumb pronounced Cratchitt ever so eensy-teensy bit like Craptchitt stuffing an extra “T” in there.

"Craptchitt, crappedchitt, crappedshitt, crapped shit..."

He was playing with comedic fire. Not only a wild-eyed little madman, he was also an out-of-control giggler. The name nearly took him out of character, but he remained firmly rooted in family shame and repressed anger.

The performance ended with Tiny Tim, the only boy in the sixth grade shorter than Adam, dropping his plastic turkey fork and flubbing his one line.

“God save us, every one!” Tiny Tim wailed, backing away from Scrooge in fright. Meanwhile, Mrs. Somebody-or-Other comforted Ms. Crosby crying in the janitor's office.

In lieu of a final bow, the little madman mounted the ice cream sandwich table and tore off his pom-pom hat. "I can act! I can act!" he cried, throwing radiator pennies into the air like wedding rice. The vice principal had to flick the cafeteria lights repeatedly to bring the performance to a conclusion.

While there was no question Adam needed firmer direction, it was hard to disagree that there wasn't something dramatic in the lad.

*

Much later, summer of his Freshman year in college, Adam hunched over his Olivetti typing up his screen test resume of fictitious parts — Oliver in Oliver, Zorba in Zorba the Greek, Rosencranz in Rosencrantz & Guildenstern, Tevya in Fiddler on the Roof. These weren't even plays he'd seen.

He crammed so many dazzlingly lead roles onto that resume, he could have memorized the Talmud with less effort. Not a thing on Adam’s resume was real, certainly not his height.

Well, one thing was real. All the way down at the bottom of the resume he included “Ebenezer Scrooge, A Christmas Carol.” No date or theater was indicated. True, the childhood credit was unlikely evidence that he had acting in him, but it was still evidence. He’d pulled it off at least once before, and he remembered the feeling.

Yes, he did.

Confidence is a curious thing.

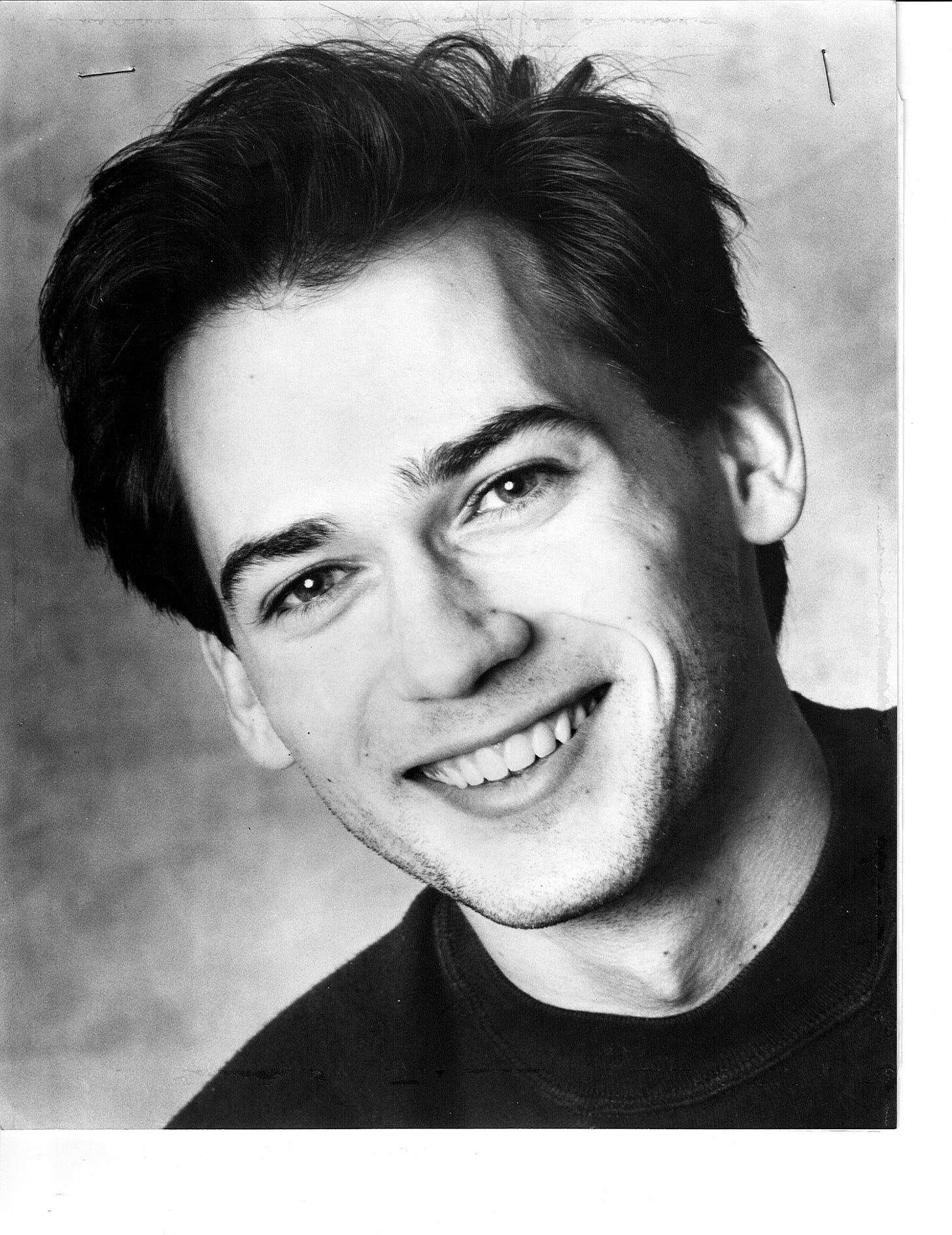

Chapter 3 — The Headshot

My father took the headshot in the bathroom. The photographer’s backdrop was the blank white surface of the shower wall. We put the back porch step stool into the tub so I’d have a chair. We dragged lamps in from another room. By “we” I mean “I.” My father was allowed inside my mother’s apartment to take the picture, but not to roam beyond the DMZ of her kitchen and its adjoining bathroom.

He was not an easygoing man, my father, but this sort of mission brought out something adolescent and playful in him. The task took some of the daring and panache (one of his words) that he admired in others. The son’s audacity with the ten screen test gambit was a validation of himself, particularly as he had been enrolled as a partner-in-crime. This was rare.

Generally speaking, I did not involve my father in any of my activities other than proofing college essays and seeking his blessing on newspaper editorials. There was almost no overlap between us, no shared history or interest in skateboards, electric guitars, rock concerts, or high school girls in back seats. These interests were my lifeblood, but they were alternately mysterious or inconsequential to him.

But the afternoon of the headshot, we had overlap. We were doing something mischievous and cool (one of my words), a word he would have struggled to define, but “cool” must have been what he felt pulling the cardboard top off the box of headshots a few weeks later.

He felt what I felt that day at the printer’s. I know he did. He was, at the end of the day, my father.

*

My mother was not in the bathroom as a co-conspirator, but she would have been within eyeshot of the bathroom door.

The layout of the home is relevant. Our apartment was on the first floor. After the divorce of my parents, my mother purchased the home with her inheritance, and she rented out the second floor to maintain the mortgage. By the afternoon of my headshot, my parents were long since divorced, but they were reliably on and reliably off in a sine wave of platonic relations. That afternoon, they must have been at full moon in the waning and waxing, otherwise the son and his father would not have been crowding lamps into the bathroom or back porch stools into the bathtub.

But waning or waxing, there stood an invisible wall between the kitchen and the rest of my mother’s home, a barrier my father was never allowed to breach. The cost of defending her financial and psychic walls led to the ulcerative colitis that staggered her at regular intervals before it took her life twenty years later, but my mother could compartmentalize people, ideas and time. You may laugh at my kitchen table, Barry, but not within my living room.

Their on-phases were a respite: Saturday morning badinage at the kitchen table, my father arriving to pick up his children, parked where he was allowed in the back driveway, my mother’s loud laughter fueled by attention from Barry, my father’s chuffed calm, trousers (his word) casually crossed, his settling backwards an extra degree, the slowed tapping of his Chesterfields.

His voice changed when he was comfortable, when he was the center of attention, holding court. It found a burr, a purr, something sophisticated and unusual that my mother must have adored in their early years. The two of them could banter with each other more intensely than with anyone else in their too-brief lives. Neither backed off their opinions for each other, not a hair, and agreeing or disagreeing, they had the benefit of a marital shorthand, and they had shared interests and references and intellectual gifts. They had overlap.

They were moons sharing the gravity of some dim planet. And when my father lay dying from cancer a decade later, my mother moved from Oakland to Minneapolis to care for him — and, still the two waned and waxed. The same flashpoint battles and platonic truces broke out again, this time in the DMZ of my brother’s home. They laughed, they stormed in, they stormed out, and then they conversed for hours on his deathbed, my father beneath the sheets, my mother above.

And sometimes, quietly, the two of them sat side by side and read.

*

In the last year or so before the fallout of their marriage, and over a decade prior to the afternoon of my headshot, my father became an avid photographer for a season.

Even as a six-year-old I knew that my father owned a “Nikon,” something best-in-class, something rare, a marvel of mass and green glass and rotating knobs and latched chambers that I was too young to be trusted to hold. (Even with the strap draped carefully over my head, even then my father held the camera for his younger son — if not from him.)

But I was invited to peer through the porthole eye rubber to look into his precision world. And even if I didn’t understand what I was being told about Nikon lenses, when the camera was angled right for the fleet sighting, I saw something marvelous in there that was very much my father: twitching black levers with hollowed circles, intelligent decimals, something sandy, matted and dim on the canvas of that miniature screen. In that crisp darkness, I could see the mechanical, pristine elegance inside my father.

Awe. He was showing me Awe. This he did understand about fathers and sons.

Other than the actor’s headshot he took on this afternoon many years later, though, I can’t recall a single other photograph of his. Photographs weren’t the point.

*

My mother sitting in the DMZ outside the bathroom on the day of the headshot would have had time to think — and too much of it. She would have remembered my father’s earlier pictures. Two of them in particular.

These were not the first headshots my father had taken of his children. He had taken passport pictures of my brother and me — in secret — directly before the collapse of their marriage. We were six and eight. Scotland, I believe, would have been the destination. For that photo shoot, the white living room wall must have been the backdrop. In the end, those two headshots were never used. My father had the daring to take the two pictures, but he lacked the courage for the deed.

For my father’s sake, I wish he’d gone and done it. His life needed one wild act of pure bravery.

Let it be a kidnapping.

*

(Oh, how my mother would have howled with good-natured laughter at the image of Barry kidnapping anyone. My father at that kitchen table would have closed his eyes, shaken his head, and, bemused, pretended not to understand.)

*

As for my mother sitting tight-lipped in the kitchen during the photo session — she would not have been supportive of the fraternity mischief playing out in her bathroom. Whatever this male thing was, it threatened the handhold-by-handhold achievement by academic certificates that she trusted and had benefited from. A bathroom headshot and a fake acting resume were cheating to her, anathema. Acting in movies should follow years of acting on the stage and training and study and, inevitably, reading.

My mother herself was at times spectacularly courageous, but she was not the joyful possibility that shines through in acts of daring. There’s a difference between courage and daring, and my parents lived across that gulf. My father dared to take the pictures when she was out one afternoon. My mother had the courage to steal the children off to Italy with no money and no husband.

Later on, after my own daring had paid off, I could see that my mother loved my work in film and, in spite of herself, deeply admired her son’s chutzpah (her word). Undoubtedly, this was possible because she was no longer afraid for me.

*

And yet, Adam… and yet…

My mother was in the bathroom photography studio. My mother was the parent that loved the movies.

She would spend her last five dollars to sneak out and see a foreign film with me. We would rummage and pilfer from our separate coin jars as accomplices. She’d pencil out IOUs until Friday’s paycheck to pull off a trip to the movies. The rides to the foreign film theater, miles and miles away, with the radio blaring or the two of us swept away in conversation, were our mischievous joy. We had overlap, my mother and I, and a great deal of it.

In these films my mother loved, there were no dreams too far. She would have wept with delight for a character with her son’s audacity and, later, with her same unbridled movie theater heart, she would have cheered that character’s courage when he pressed on in his accidental career.

In the darkness of a movie theater, it was safe for her to pretend and to weep with delight for proxies of the ones she loved. Actors were her People, and in the iridescence of movie light my mother freed her hummingbird soul.

*

To understand what happened to my acting career, simply know that I carried the one, the other, or the both of them into every audition, and from every director’s cry of “Action” to every “And Cut.” The two of them ran wild in my psyche, ranging room to room in the red bloom of argument, waning and waxing, castigating each other in marital acrimony, but, also, at times certainly, leaning back at ease in the kitchen wiping tears of laughter from their eyes.

I had my successes, significant ones, but when I failed, I felt the gravity of their moons. I was tugged by my father’s “I can’t do it” and my mother’s “you shouldn’t try.”

Both of my parents would have had it otherwise and wept to read this, but they were not coaches for a dream team that came in first, and I was not a dream team player.

We didn’t act, and we didn’t play.

Chapter 4 — The Extra

Right after we moved to Brooklyn six years ago, I was walking with my family under the DUMBO overpass, and I oh-my-god-suddenly-realized that it was in the Lost Film Location, a location I could never remember other than “somewhere very dangerous in 1984 Brooklyn.” I was a crowd extra under a bridge in a music video. The band was unknown. The song was called Life on Earth. It was my first time on camera.

But, oh, the relief of solving a forty-year nagging mystery! This, my grown children, was the day I melted my fingerprints off waving a Bic lighter in the air for twenty-two hours.

I never tire of sharing this when walking beneath it with my family.

Me:

“It is like passing through a time portal.”

My Wife:

“Yes. For me, too. You say that every time we walk under the overpass.”

Me (ignoring):

“This is the archway where the band was playing on a stage, and the extras were put in, like, a bullpen over here, or maybe it was over here. I’ve lost my bearings. Can we stop for a second? It’s incredible. It’s the Lost Location!”

Ungrateful Child, the Elder:

“You made a $1 an hour and the band wore paper mache alien heads.”

Ungrateful Child, the Younger:

“One of their heads fell over sideways like a broken corn stalk."

*

There’s no job on the planet that requires less skill than being a film extra, and I include museum guards, and a museum guard still needs to be able to throw himself between a masterpiece and an animal rights activist.

If you don't have to go through 18th-century hair and makeup, being an extra is the lowest stress job in Hollywood. You can start your career the moment you can legally work a 20-hour day — for non-union this is three months old — and then you can ride that $80 a day pony all the way to your death bed.

Other than a couple of hours of day of “work,” the last thing you want to do as an extra is “anything at all.” You want to sit and snack. And your employers are okay with that. If you turned into a prop department stop sign between takes, they couldn't be happier. The whole career is a glorified game of red-light green-light.

Green light:

“We need background on the set… and action”

“You there, yeah, you: run ten feet, shake your fist and then chase the girl motorcyclist who upended your fruit cart.”

Red light:

“Cut.”

And voila! You’re a prop department stop sign.

Snack table.

Green light:

“There’s a hair in the gate. Reset the fruit stand. We’re going again.”

“Oh, for fuck’s sake. Really?”

*

It’s not just about the money. In a full career you might get to punch a blue-screen monster in the knee cap, knife into a rubber steak, or crash repeatedly through a sugar-glass shop window a good 150 yards behind the real actors.

The worst thing you can do as an extra is act. Oh, my god. If you are an extra and you start acting, you will be placed so far into the background you turn into a bald spot.

And woe betides these Thespians unloading great duffel bags of make-up, dog-eared volumes on method acting, curling irons, and high-grip Spanx onto their grey folding chairs. At 4:53 in the morning they are pinning SAG cards to their astronaut costumes, spray painting their bald spots, and working their way through vocal exercises at Shakespearean volumes: Lallery, Lillery, Lollery, Lullery. Oh, for a Muse of fire! Heavens of invention! The sound! The fury! And the strutting!

(But Blessed Are the Extras that work themselves to the front of the music video with elbows sharper than the spiked wheels of gladiator carriages for they shall be Visible.)

Green light:

“We’re going again.”

“Oh, for fuck’s sake. Really?”

*

The Old Timers know this is the best job in show business. By Old Timers, I mean anyone who has been an extra for more than three days. They know the lowdown. First thing on the set in their morning, Old-Timers are filling their empty knapsacks with food pilfered from the craft services table.

They make runs to the liquor store, get high in the port-a-potties, and check if adding “comma asshole” to the end of the bag lunch Chinese fortune cookies is still funny on the third day of the shoot.

“Haha! Yes! Mine is! Try yours!”

“All your dreams will come true comma asshole. Now you comma asshole!”

“03 14 27 29 32 54 comma asshole.”

“High five!”

This is definitely not sitting behind a boring old desk. What a job! What if you could go back and tell your ten-year-old self that this is what you will be doing someday?

*

Break by break they storm and norm and form and burst into tears reading their resumes to each other. They steal “that guy’s” bald spot spray and paint Hassidic beards on each other’s headshots, remove screws from the folding chairs, sneak past power truck Teamsters asleep in lawn chairs, slip into the costume trailers, and, giggling like eight-year-olds, navigate blindly onto the set wearing, if I remember correctly, stolen paper mache alien heads.

“Hide! Hide! We’re fucked! You dented the head! It’s hanging halfway off your neck! Run comma asshole! Run! The drummer’s coming!”

*

But the best thing — the absolute 100% best thing — about being an extra is being treated like a complete idiot. Because being treated like a complete idiot in a group of other people that are also being treated like complete idiots, is a recipe for horseplay and hijinks! You find you’re turning your eyelids inside out at thirty years of age, firing soda from your nose for the non-union infants, and, whoops, vomit laughing. Imagine being paid to be in 7th grade music class with zero risk of being sent to the principal’s office.

Green light:

“We’re going again.”

“Oh, for fuck’s sake. Really?”

*

My music video never made it to MTV. Maybe it was the crushed alien heads, but I never had a better day on a set my whole career.

“Honey, wait up, I think I just found the place where I was in the music video.”

Chapter V - My Second Father

The character was Paul Pierce. “Irreverent” the Backstage advertisement read. The film was called Amateur Hour, later to be retitled I Was a Teenage T.V. Terrorist.

It was my first audition, for a lead role no less. The word “irreverent” jumped out in the character description. Irreverent I could do. Irreverence was a sweet spot.

I didn’t have a monologue prepared, and I wouldn’t have known where to find one on such short notice. So I wrote mine. Then, typewritten script in hand, I paced back and forth in the fraternity basement, jumping onto and off a collapsed sofa memorizing it, acting it out. I stopped cold from time to time listening for footsteps that might be coming down to the basement to figure out what the hell all the drama was about.

My monologue certainly fit the bill for “irreverent.” I covered clever graffiti in university bathroom stalls, leather jackets for reasons that now escape me, cigarettes on toilet paper dispensers, fire extinguishers, electric guitars, and — with a soupçon of irreverence — the heady topic of masturbation.

My monologue might have been funny. Oh, fuck it. It was funny. Very funny. They should have fired me from the starring role and hired me to punch up a lifeless script.

If I hadn’t had a fever the day of the first audition, I might have never gotten the role. The fever helped me operate at a much higher level of “don’t really give a damn” than I normally might, and the combination of fever and crude hilarity was my ticket.

My knees might have knocked, but I made them laugh.

Oh, how they must have imagined their audience laughing like that for ninety plus overprinted 16mm minutes! “We found irreverent Paul Pierce!” But to be good in the film, I would have needed a fever so powerful it toppled Paul Pierce into a coffin at the wrap party.

During that first audition the producer told me, unforgettably and with a dazzling smile, that she had “friends at Paramount” interested in her $250K film. Looking back she had her own rehearsed monologue. They were bullshitting me as much as I was bullshitting them.

“Yay! The movie business! Welcome! Come on in! The water’s warm!”

Suspiciously warm.

*

Within a few weeks I found myself on the set of Amateur Hour for the first day of shooting. I stood behind a fake apartment wall waiting for a director to call out “action” that first time. My costar stood behind me. We both carried empty suitcases. We were moving into our new apartment sight unseen.

I’d been through costume and wardrobe for the first time that morning. A beautiful Canadian make up artist dabbed me with little square sponges. An A.C. measured off the distance from my eyes to the lens without making the slightest eye contact. A sound boom hovered above me. From the bottom of my field of vision I could see my taped actor’s mark on the floor. My mark ended up bringing me closer to the camera lens than I’d expected.

There was quiet on the set.

Only actors really know the quiet of a movie set, and every film actor must remember the surprise intensity of the first time they step into it.

Your entire being needs to fill that quiet: your voice, your mind, your heart, your body, and at times your stillness. That silence is as real as silence gets. It is pregnant. And I am standing in it after a few quick weeks of rehearsals in a Greenwich Village apartment.

Everyone is staring at me, waiting for me to do my job and fill the silence with something, anything memorable. Even on a small set there are many, many people staring at you.

I am in this strange aquarium for the first time, my thoughts bubbling madly, everyone hoping to discover a beautiful fish.

*

“And action.”

“Are there lights?” Paul Pierce asked, hitting his blue tape mark.

“Lights? There must be lights. Track lights…” said Rico, the Puerto Rican superintendent.

*

Amateur Hour taught me that there are things I couldn’t achieve through arrogance, focus and will. I couldn’t make myself smile on cue or laugh or cry or amuse. And even when I could do those things once or twice from this camera angle, I couldn’t do them once or twice from the next. Or I could do them in the first call back, but not the fourth. Repetition became a hell.

I learned under enormous pressure with a crew standing around me that there are realms where you can’t “fake it till you make it,” and all the mustered arrogance, focus won’t get you there. You are either a pretty clown fish outside the little plastic castle or you are not. I was not.

Or I was, but I could not come out.

I learned in that same crucible that the movie personality I wanted to be — assumed I would become — was not at all who I would turn out to be. It was like catching sight of someone ugly in a mirror and realizing it’s you.

I thought I’d be a movie star, someone cool, someone I would have admired, punching as he punched, kicking as he kicked, screwing as he screwed, but instead I was this other guy, and one I wouldn’t have liked at that.

Worse was the rising and very real possibility I was that guy off camera, too. It was disorienting and brutal. Imagine watching your every recorded movement and sound with the same confused, even repulsed sensation that you might feel hearing your recorded voice played back. Is this really me?

(Yes, that is really you. Now you know.)

Amateur Hour, and my acting experience at large, taught me, cruelly, that failure can be public and permanent. Shame is waiting in the wings. When you get yourself that far out on stage in anything in life really, and certainly in film, that you better be really good, because if you are not — and when you know it — nobody in the world will be crueler to you than you will be to yourself. It doesn’t even matter if it true.

I was horribly cruel to myself, and cursed the arrogance, focus and will that got me there. Praise for my acting from any quarter was like being splashed with hot acid. That someone loved the ugly, uncool guy was further insult to the injury. “That’s exactly what your voice sounds like, Adam.” He is you. That actor is you.

And there are no actors. Isn’t that right, Adam? Wasn’t that the game that we were playing? That he would be you, the audience punching as you punched, screwing as you screwed?

Somebody who doesn’t get this will let me know after reading this that I was actually wonderful, and they will try to prove it to me and prove to me that they loved me.

Hot acid.

Worse, there were people who saw me exactly as I saw myself. They didn’t like me either. All of this was a dark confirmation. Imagine the vulnerability.

There was a stretch after one movie opened when I was so ashamed of a performance that I hid in my fraternity room for a month, failed classes for the first time in my life — including, laughably, a Pass/Fail acting class — and a concerned dean placed me on academic probation. For a decade I could have given a valedictory address on Shame and Never Taking Chances.

“When you’re out there, Class of ‘87, I mean when you’re really, really out there — the price of failing will be very high,” I would tell the openhearted.

“Hide.”

*

But now and here — for a single time and publicly at that — let me recognize the pure, youthful audacity of it, the bet, the monologue writing, the bullshitting, and the pulling it off. Because it is amazing I did it on arrogance, focus and will, and the life experience from it, by any reasonable measure, was exceptional. I won the bet not once but twice in those first few auditions. Two roles in the first five auditions. My God, I pulled it off.

But my acting career has to be more than winning a bet. It has to be. I still must be missing something right in front of me.

Somebody please help me without scalding me with hot acid.

*

You were first in one movie, and then you were in a bunch of them. You were the movie sidekick of a Golden Globe winner for Best Supporting Actor in a boxing film by 20th Century Fox, and then you had a 1:1 scene with Michael Jackson, the most famous man in the world at the time. You high-fived Michael Jackson.

America’s greatest director, Martin Scorcese, asked you if you were happy with a take when you worked with him — in a brief way, you could say “collaborated.” Quincy Jones watched from the sidelines.

Woody Allen told the best casting director in the business that you were great in an audition for him, perfect for a part. The whole reason you were there was simply because she wanted him to meet you.“ That was great, Juliet, right?” Allen asked.

You signed autographs for strangers whose hands trembled passing you pens. You co-starred and then dated the sexy red-headed girl you’d seen in an R-rated movie in high school.

You opened fan love letters from Argentina and Japan. At your old prep school, a former teacher sent you a delighted letter that he’d seen your picture pinned on a cork board in a student’s room.Your agents battled to sign you, and then they told the losing agencies to keep their distance, and then eventually to fuck off in an irate call you watched from the sofa in their office. Afterwards you laughed with the promise of a star-bright future.

You were reviewed in the New York Times by Janet Maslin — in passing, but warmly enough to clip for posterity. To this day, a few last stragglers on the Internet wonder what happened to you and marvel in the comments of stray online posts at “how someone so talented could have completely vanished.”

And finally, and most importantly, you were sent two different letters years apart from fans that told you your performance in Parting Glances — your groundbreaking film on the AIDS crisis — kept them alive through the hopeless agonies of being unloved and desperate gay teenagers. Somehow they found your address and wrote you because they needed you to know that. They wanted to thank you. Both times. Same story.

How many others? One? A hundred?

*

A fire blanket of shame extinguished pride in any of it, but it all happened. And it’s not nothing.

Good for you, Adam.

You did it.

Chapter 6 — The Giggler

When I first met my second father, I giggled uncontrollably.

I was eighteen. It was the third day of shooting. My exasperated second mother had kicked me out of the house in the suburbs, and I’d moved to New York City with my first girlfriend. My first movie director was, umm, displeased with the out-of-control giggling, and my first movie producer started to worry about her first “Paramount” film.

In our first scene together, no more than sixty seconds in, my second father lifted me from my chair by my thick brown corduroy lapels and yelled in my face. Big ballbuster Marine eyes. Very, very wide and an only pleasing from a distance Germanic blue. Flecks of drill sergeant spittle were the least of my problems. He got bulldog close to my face, and I’m trying, trying, trying… to hold it, hold it, hold it…. then slipping, slipping, slipping… acting now the least of my problems…

“Tee-hee, tee-hee.”

“And cut.”

By the seventh take my giggling was like clockwork. Every time my second dad promised my girlfriend and I that we would start “at the bottom… below the bottom” the giggles pounced like adorable kittens with tickly little claws.

“And cut.”

If I survived the submarine attack of spittle-giggles on the words “below the bottom,” then I blew apart on “Now you listen to me, and you listen to me good. When you come into this office, I talk and you listen. Your entire wretched generation has poisoned itself with narcotics and abominable music.”

And… wait for it…. wait for it… everyone on the set wait for it… Producer and director wait for it… it’s coming, coming, coming… hold on…

“Tee-hee-hee…. oh, tee-hee-hee…”

“And cut.”

I blew apart as predictably as a SpaceX rocket.

“One more take. It could happen to anyone. Let’s settle down for this one, please.”

“Focus, Adam!” scolded my fourth girlfriend who, any neutral party could agree, should have been more focused on memorizing her lines.

And… everyone looking away now…

“Oh! Oh! Sorry! Oh, tee-hee.”

“And fuck, fuck, fuck. Cut.”

Twenty-seven takes later we were approaching the we-can-only-afford-three-takes bad-film-acting-budget-completion barrier.

“Sanford, how about I make him cry first? That might free up our afternoon,” my second dad asked my first director.

“Shame and giggling are next door neighbors,” offered my first girlfriend looking up from Acting for Dummies.

“Sanford, you need to handle this,” said the first producer. “The whole film can’t be one long blooper reel of your actor laughing uncontrollably.”

“My actor?”

*

On the spectrum of talent, every one of the non-union actors in that film could be placed somewhere in the ROYGBIV hot red zone. To an actor we were reliably between extremely poor and hopelessly okay. After a week of lifeless footage, our best hope was to “shoot the moon” with all bad cards to borrow a metaphor from the game of Hearts.

With the exception of my second father, John MacKay. Sadly enough, he was good unfortunately — a high ace — and he blew the perfect bad hand.

You hear about actors working with stronger actors and the stronger actor carries the lesser actor. The lesser actor automatically gets to be better in a scene. Imagine, say, working with Meryl Streep and she’s so real and responds to you so organically that you forget you’re even acting. No offense, but even you could do it, hot stuff. These actors practically bring a weepy soundtrack. It was like that with John except he was yelling at me, and I believed it, and he was too real for me to stay in character.

Every time Second Dad circled his wooden executive table and started angling towards me, I found myself watching a film, not acting in one. Or I forgot my lines. Or I was frozen in awe. Call it “teenage terror.”

Sure, maybe a few times for a second or two John MacKay helped “merylstreep” me into the world of make-believe, but I fought back. I managed to giggle John all the way back over my tug-of-war line into theatrical unemployment.

“And cut.”

“I think we have to go with what we have, Sanford. He didn’t giggle on that one.”

*

Towards the very end of filming there was one last night shoot.

My second father and I got to joking off set, and we wound ourselves in stitches laughing about Little League baseball. I made a joke about talentless right fielders too busy picking daises in the outfield to notice baseballs rolling up to them and stopping dead.

My second father laughed so hard he began snorting and wiping tears. (He was a snorter not a giggler.) Over the years I have repeated that joke about right-fielders picking daises but not a soul has ever found it the least bit funny. Maybe it was an inside second family joke.

But I have a hunch it wasn’t. Maybe his laughing at my jokes off camera was really an acting strategy for our relationship on camera. Maybe I was being manipulated like some 1930’s director telling Shirley Temple her puppy died (who, while extremely charming, was also something of a giggler.) This is my hunch because that night there was a third-act reconciliation between our father and son characters, and for one reason or another in the script he now admired his Teenage TV terrorist son, and he had one last scene that evening to prove it.

Or maybe it was genuine second-father-second-son camaraderie, but for a few minutes way, way out there in right field by the losing team scoreboard the Hysterical Teenage Giggler second son made his Big Bad Marine second father laugh.

“And cut.”

Now that was the scene Sanford should have captured on film.

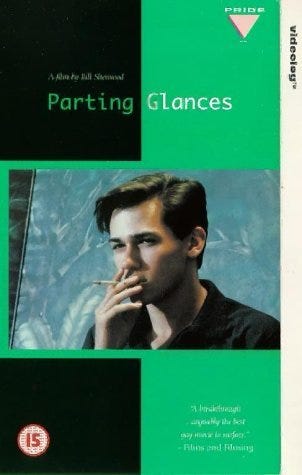

Chapter 7 – Parting Glances

It couldn’t have been a smaller part, a few lines at best.

I was offered the role of one of three townie teenagers harassing Steve Buscemi’s character out on Fire Island. The film was Parting Glances. Steve Buscemi wasn’t even “Steve Buscemi” then — although he would be after the film came out with rave reviews for his performance. If there were parting glances for anyone in this film, they were from Steve looking back at his career as a NYC fireman.

As I had with Amateur Hour, I found the casting notice through Back Stage magazine and submitted a headshot. It was my second audition and again, incredibly, another bite. (I was still in the early days of beginner’s luck. You can’t imagine how easy I thought all this was.)

The filmmakers were ambitious: it would be the first film touching on the AIDS epidemic, a real film I was assured, not some kind of other film I might regret being associated with for the rest of my life.

There was a lot to consider. In 1984 when this was casting you could still count on two hands dramatic films exclusively about gay leads. Hollywood films spoke in code and films about gay characters were rare. Films about gay characters not tormented about being gay were even rarer.

And there was more: Auditions through Back Stage were a mixed bag. Imagine Craig’s List for actors. I had no script and zero idea what I’d be getting into. There were only a handful of lines. The part carried some level of professional and personal risk. I was a straight eighteen-year-old who wanted desperately to be cool. You can’t bring #2024 to this.

This certainly wasn’t a film to be cool in. On the other hand, Bill Sherwood, the film’s director, struck me as the real deal. I trusted him instinctively. I trusted the producer. And I was sympathetic to Bill’s vision for the film.

But I made my decision.

In my beginner’s luck imagination I was already much too important an actor to say yes to any part that had a pound sign after it. Parting Glances presented nothing but risk. The film would never come out, and anyway look how easy landing a movie part was.

You get every one you go up for.

I turned down Townie #3.

That I ended up in the film was a fluke.

At some point prior to the start of principal photography on Amateur Hour I ran into Yoram Mandel, Parting Glance’s producer, on a street somewhere on the West Side. We remembered each other from the audition. He’d heard I’d won the lead in Amateur Hour, congratulated me, and then told me a much larger part was now available in Parting Glances.

Apparently, they’d let the original actor for this larger role go. Mandel practically offered me the role on the spot. I hadn’t been recorded on a single frame of 16mm film yet, and look, I was already important! Cast in the street! I felt flattered, in demand, ascendant, famous! Oh, these early Midas Days that teased and then deserted me!

The newly tendered role was Peter, a gay college kid, romantically interested in Michael, Richard Ganoung, one of the leads in the film. Peter was romantically circling, waiting for an opportunity to strike when the lead’s boyfriend moved away for a year on a job transfer. It was a significant part Yoram explained — and it was. The part would later end up fourth in the credits.

“Bill will call you,” the producer promised me.

I met Bill in his Upper West Side apartment to talk through the part. He shared the script. There were scenes throughout: in a record store, at a party, on a stairwell, alone in the final shot of the movie knocking on Michael’s apartment door. I was leaning in towards a yes now.

I double checked more directly on whether I’d be touching, kissing, hugging, holding hands with anybody, brushing against them in the hallway accidentally or otherwise. I didn’t want to. I was frightened to. I had no idea of the potential repercussions. God knows what else I was worried about. I think I asked that this guarantee was in my contract. (I know. I know. I know.)

Bill assured me — again — I wouldn’t be. The closet was packed in those days, and here I wasn’t even gay! I was coming out of a closet I wasn’t even in! What the hell was I doing? Nobody really believes actors aren’t who they play. That’s half the fun making the one the other.

And — also, let’s get real — my concerns were legitimate, particularly for a budding teenage actor. Typecasting was a much bigger deal in those days. To play a gay character might be a road to playing only gay characters. Forever. Gay part, gay part, gay part until was acting in plays in a nursing home. The level of stigma around being gay was through the roof. (Even my agents later counseled against any other gay part of which there were suddenly offers. I wasn’t alone in evaluating the risk.)

Bill assured me, slowly and clearly — again, dealing with Mr. Cool Eighteen-year-old — that I wouldn’t have to “do” anything. My god, he was patient with me. When I turned away, he must have rolled his eyes and banged his forehead.

Hey, #2024, let it go. You have no idea. You weren’t there. It was different. Your generation has boys that are high school prom queens. Unfathomable.

But I also wasn’t a bigot, and I didn’t want to be numbered among them then or now, and I understood the movie was about foundational dignity. I went to college in New York City to be closer to all of this, to be near better, braver people, to fight for civil rights, for dignity. To run would have been moral cowardice. That felt like a line you can’t uncross. And here I was.

“I’ll do it.”

*

Parting Glances was a success out of the gate, initially with the gay community and then expanding immediately to a far broader audience. The film struck a nerve. Gay men — and gay women — walked a little taller coming out of the theater. It played for what felt like ages at Embassy 72nd Street opposite My Beautiful Launderette, the Embassy one of the three major art house theaters on the Upper West Side. Possibly later at the Angelika. To see posters for my film at the front of a theater that I went to regularly was a life milestone. To see people lining up on the street at the Embassy was surreal. To have people approach me on the sidewalk and tell me how much they loved the film was incredible really. This went on for years.

There were other milestones, uglier ones. The reception on the street wasn’t always warm. These were the early days of AIDS and “the gays deserve it.” And the key word in those quotation marks was reserved for polite company.

A guy in a bodega in the Village came up to me once and told me with seething contempt that I was in a “freak show.” “Why are you in that freak show?” The words were burned into me. And that was just one guy who was miserable enough to approach me. If I hadn’t been scared of him, I would have asked him why he went and saw the film in the first place, but striking so close to a nerve would have been dangerous. I hope he knows that it’s safe to come out now.

That miserable encounter was a taste of the thing I despised and believed New York City would be better than. It was the briefest glimpse through a window into the contempt gay people have to put up with.

That encounter only made me prouder to be in the “freak show.” It raised some dormant defiance. Fuck him. Fuck all of those people.

And fuck all of you now.

*

For years Parting Glances remained on Top 10 lists for gay films. More recently it’s been crowded out in these lists by big budget mainstream films with exotic locations and movie stars that a little indie film financed scene by scene couldn’t possibly compete with. At one point I was gifted a great coffee table encyclopedia of 20th Century film and Parting Glances was in there for the year 1986, another milestone. The gift giver didn’t even know it was in there. They knew I loved the movies.

Parting Glances launched more than Steve Buscemi’s career. Kathy Kinney emerged from it to become a television star on The Drew Carey Show. John Bolger worked for six years on General Hospital and a number of commercial films and more recently The Only Living Boy in New York. I had my own more modest successes afterwards. They were smaller, but they were genuine.

All of us have Parting Glances and Bill Sherwood to thank for that.

*

Strategically, Parting Glances wasn’t selling a “we’re here and we’re queer” message. It wasn’t a clarion call. It wasn’t strident. It certainly wasn’t ACT UP. I stated more simply “Yes, we’re here. This is us. We’re not a freak show actually.” For some viewers maybe there wasn’t enough “here and queer.” I’ve heard complaints about the film that the gay community represented in the film was “straightwashed.”

Possibly.

None of the major characters were “flamboyant” or whatever word captures the thing you know I’m getting at here, and three of the top four male roles were played by straight men. In many ways the vibe was wealthy Manhattanite yuppie with Steve’s role a rock and roll star, a different direction altogether.

Incidental characters were undeniably gay, “types,” and they add a great deal of atmospheric color to the film. In my take on Parting Glances, Bill was saying, insisting really, “We’re here. We’re living complex lives with complicated, tender, committed romantic relationships, beloved friends, sophisticated music, and, you know, fuck it all, laughter.”

That and “oh, we’re dying.”

Janet Maslin in a lukewarm and largely sniping review made a point of this in the New York Times. I know the review upset Bill. He must have wanted a warmer welcome in his home town. Maslin was kind to my performance, if fleetingly, and she made a generous concession to Bill’s overall handling of AIDS. The review was better than it could have been, but there were good reviews aplenty elsewhere.

The Washington Post got it spot on.

More recently, Lit Hub is very generous with its assessment of the film and my own performance.

Quentin Tarantino all in on Steve Buscemi in Parting Glances. It was the catalyst for Buscemi’s role as “Mr. Pink” in Reservoir Dogs.

“It is to both his (Steve Buscemi) and the film's credit that the anguish of AIDS is presented as part of a larger social fabric, understood in context, and never in a maudlin light.”

– Janet Maslin, New York Times

In the early 1980’s, our President wouldn’t acknowledge the AIDS epidemic existed. Not a peep. This reluctance coming from a former actor no less. Shame, shame, shame on Ronald and Nancy Reagan. Think of the gay actors he represented as the head of the Screen Actor’s Guild only a few years prior — many of whom were undoubtedly close friends. Talk about double lives. But to surrender to his prejudices or his constituencies or both, there was no federal funding in the fight against AIDS until 1986 the year Parting Glances is released. Think of what we’ve just been through, and this is incomprehensible.

The death toll was staggering. It’s drifted too far from the popular imagination. By the advent of the antiviral cocktail drugs in 1995, I’d lost my agent, my manager, three friends at a single restaurant I worked with in Beverly Hills, and who knows how many others in my close orbit died that I never heard about.

These were people I cared deeply about or simply knew or worked with and divided tips with and shared drinks after work, and laughed at funny impressions and double-dated, or acted with in films, or went to their plays. They slipped away often privately, emaciated, lesioned, of course terrified, and far too often in shuttered silence.

It was ghastly. I don’t have a better word for it.

*

Two of the many deaths that will haunt me forever were taken from the young. Teenagers. There was Frankie who made the espressos in the back at that Beverly Hills restaurant. He was about the sweetest, gentlest kid in the whole world. How else to put it but “everybody loved Frankie?” Everybody. He couldn’t have been twenty when he died. Jesus Christ. RIP Frankie. In my mind’s eye I can see your face even now.

And another kid: a kid I never even met, a voice. I heard him for a minute or two. He was a high schooler who called into one of those Love Line shows on the radio. He explained he had sex one time with a guy at his high school. It was the first time he’d ever had sex and he contracted HIV. The kid said, “I don’t even think I’m gay.” It was “one time” he repeated until I wanted to crack. Every listener in the Tri-State Area must have felt the same. He couldn’t get his mind around it. The “one time” was somehow a key to making it end, but the key opened nothing.

This boy wept on the phone, and the radio host had nothing to comfort him with.

That was AIDS. It was a riptide.

“Still, Sherwood offers an intelligent alternative, sure to be a welcome relief to gay men who are sick of TV movies about getting AIDS or telling the family the awful news. Here there is nothing particularly odd about gayness. The youngest character, a record store clerk, told his folks when he was 16. He wants a normal life, he says, "a co-op on Central Park, a BMW, a house in Bucks County.”

— Rita Kempley, The Washington Post

*

And then Bill died, too.

He hadn’t contracted HIV when he created the film, and he never got to make film #2. The last time I saw him he paid me the last of my deferred payment for my role in the film. (This was its own saintly act. Nobody bothered with deferred payments for actors in indie films. That the film was released was your payment.)

Bill also gave me a manila envelope with clipped reviews for everywhere I was mentioned. He’d cut them out and saved them for me. I’m sure I must have thanked him, but I was far too self-absorbed to appreciate his generosity at the time.

The two of us were standing on Broadway somewhere in the 80s, outside a Chemical Bank. He was telling me about his next script, something about a classical composer maybe. He was struggling to get funded, deeply disappointed, but memory may be failing me here.

And then he was swept away, too.

*

Several of the locations we shot in must have been in apartment buildings of friends of Bill’s. Costume and wardrobe changes were conducted in cordoned- off bedrooms. Some of the decor, paintings, sculpture were, at times, eye-poppingly “Agador Sparticus," and I would not have been surprised to see men playing leapfrog on the Birdcage china. This was not a world I knew or fit into.

I was a stranger in a strange land.

And the male power dynamics were different than anything I’d ever been part of. By today’s standards, at least some of the interactions were solidly #metoo, the teasing sometimes condescending and occasionally crass. All of this a sexual dynamic I didn’t understand or know how to manage artfully. But, all of us had thicker skin then, and honestly, it was the furthest thing from traumatic. It didn’t seem to have anything to do with me. Not really. This might have been fueled by my age and pretty boy role in the film, or it might have been fueled by me turning out to be straight. An imposter? Or it might have just been Me. Probably Just Me.

Or I could be wrong about all of it.

The scene was foreign to me. I was never at home on the set, but then it wasn’t my home. If I had been gay, good Lord, I would have been in a small and remarkable heaven. It would have had me sending breathless letters back home to some secret friend in Kansas. “You have to move to New York! Oh my god! Saturday! The sculpture in this guy’s apartment!” For some rural escapee, the community would have offered a rare pocket of security and freedom, an oasis, a lifeline.

I was taking up space there. I know I seemed aloof to many, including one of the stars who shared his criticisms of me publicly — and hurtfully. I believe he read me incorrectly and unfairly.

*

Anything resembling homosexuality that I previously had any visibility to was different, distant from my world, a few friends or acquaintances of my parents, the odd, suspected teacher, the odd, suspected movie star, Elton John! The Village People! Poets!

You laugh, #2024, but you’re as ignorant now of all of this as I was then.

I knew people that were gay, of course, but I was innocent enough not to think any of my own direct peers were actually gay (ha ha ha ha, oh yes they were, Adam). I only believed someone my age was gay if they were obviously gay, flamboyantly and bravely so.

Not a single one of my classmates at an all boys boarding school was out. Not one. What were the odds? A statistical miracle! If a classmate was called a f— I assumed it was to be hurtful, a cheap shot, not to be targeting something hidden that could be called out and shamed. It is so jaw-droppingly naive now.

The visibly homosexual in New York City were another matter entirely: gay men cruised the Village, ranged the piers on the Hudson, covertly snuck into front of bars with blacked-out windows and anvil-clanging, eye-popping names. Being openly gay was an act of courage and Rubicon Commitment, risk and repercussions. None of this is news, Officer, but I’d like it on the record.

Those repercussions could be ugly indeed. In the late 80’s a demonstrably “out” co-worker at an art gallery had the shit kicked out of him coming out of a gay bar in West Hollywood. I’d never seen anything like it. His face smashed in, a swollen over eye with great weltering bruises.

There was just “why?” and grief.

*

In New York City now there are a lot of references to the exceptional time that the 1980s were. There is an expanding mythology around the decade: exhibits in museums, videos of Madonna dancing at the Limelight, CBGBs, pictures of Keith Haring spray painting in the subways, rap artists and break dancers spinning on flattened cardboard, all of this long before their boom-box sounds emerged as rap and then, finally, morphed into world-changing hip-hop.

When I hear enamored praise for the resurrected decade now, it surprises me, like the artists and journalists now are talking about some other gilded place and time than the one I lived through. It didn’t seem all that special at the time, but it turns out it was apparently, and slotting neatly into that time and ethos was the movie Parting Glances. Now this I did know. The film — my film — played its part in the decade’s New York mosaic.

The young perpetually criticize previous generations for doing nothing, accusing them of letting the world collapse and kicking their cans into the future. And point taken. They aren’t entirely mistaken, but while we still had the energy to, my generation did accomplish something, gays and straights both and together. We notched a win. Gay people now marry each other, protect their relationships in the eyes of the law. They have their love legitimized through the courts. They can visit each other on their death beds. They share their health insurance and bequeath their inheritances. Again, Officer, write this down so I can sign it somewhere. I want this on my record.

Relevant to all of this, and without a flinch, straight men — major movie stars! — now appear as gay men in films with only the yawn-inducing backlash from the usual quarters and pulpits.

I see women walking hand in hand through the park and men kissing hello in my Brooklyn neighborhood — on the lips no less. They look like attorneys. And I barely think twice about it now.

No.

Stop.

This is not true: I still think about every single time, and I know what made it possible, and I know how precarious it all is, and I’m not sure you know, #2024.

Parting Glances is a brick in the structure that supports this. And you can find my own signature on that brick. It's small, but it’s there, distinct. I wasn't at the front line of anything, but I marched and I signed and I gave and I acted and I lent my mass to that crowd and then that crowd broke through onto the steps of the Supreme Court.

Yes, I was a stranger in a strange land, but you can find me in the Obergefell Choir in Parting Glances. You don’t even need to look all that closely.

*

But you should not be fooled, #2024.

Grim history has made it very clear that this is not a permanent state of affairs. Ours is a beautiful intermission, a respite, a pre-battle belle époque.

Fight, fight, fight, fight to hang on to it, gays and straights both. Your Rainbow Generation is beginning to move on. Give them a nod and a parting glance.

Thank you for writing these stories. I found your substack after a nostalgic moment when I thought about that kid in the stairwell saying “you ask your dick what it wants.”

I was 20 when I saw that movie and I had all the same enthusiasm as the character of Peter. I ran off the explore the world with all my young bravado, my confidence in coming out affirmed by that line.

Who was that actor, I wondered. Well I found him here, telling me how he came to portray that kid. Thank you.

I love your writing thank you. I so glad you are here and I bought amateur hour bc I needed to see more of you after PG. I love the tone and delivery of your voice. Once a star always a star.